par Mirabelle Harris–Eze

Lauréate 2024 du concours de dissertation pour étudiants et étudiantes en droit « Dans l’intérêt public ».

(Disponible uniquement en anglais)

This paper was originally written for an Oil and Gas Law course taken in Fall 2021 at the University of Calgary Faculty of Law. Mirabelle thanks Professor Fenner Stewart for his support and guidance on the first iteration of the paper. Nonetheless, Mirabelle is solely responsible for any errors.

I. Introduction

Alberta is in an inactive well crisis, and it is not alone. Similar concerns exist across the globe. Policy analysts and statistical models confirm the practical hypothesis that the number of inactive wells rises with falling oil prices.1 At issue: after having profited from high oil prices, what incentivises a well owner to abandon or reclaim a well at a loss? Who properly abandons, remediates, and reclaims a well when the well owner goes bankrupt, becomes insolvent, or simply does not pay? Who is responsible for footing the cleanup costs?

In Alberta, varying mechanisms attempt to address the aforementioned issues. A new government framework aims to enable the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) to better assess which licensees are less likely to abandon, remediate, and reclaim.2 For well owners that become bankrupt or insolvent, the Oil and Gas Conservation Act provides that the defaulting “working interest participant” (WIP) may be paid from the Orphan Fund.3 This fund may cover suspension, abandonment, remediation or reclamation costs but the WIP remains legally liable.4 The Orphan Fund is financed by industry levies and managed by the AER, and similar funds are found in varying jurisdictions.5 These strategies are not novel; what is novel about Alberta’s issues with inactive and orphaned wells is the sheer magnitude of the province’s estimated end of life obligations – potentially $58.65 billion and upwards of $260 billion in a hypothetical worst-case scenario – as contrasted against Alberta’s minimal security bonds and public subsidies, lukewarm enforcement measures, and limited regulatory mechanisms.6

This essay explores how the Alberta Energy Regulator, in managing oil well licensees’ end-of-life obligations, mitigating risks, and advancing the polluter pays principle, ranks in the context of regulatory excellence frameworks. In evaluating the Alberta Energy Regulator’s response to the inactive and orphaned well crisis, this paper also discusses the Government of Alberta’s new Liability Management Framework and enacted statutory reforms, regulatory limits, regulatory capture, and third-party recommendations. The paper ultimately concludes that the AER, in regulating inactive wells in Alberta, falls short across numerous regulatory excellence attributes.

II. What makes a regulator excellent?

The AER’s enabling statute, the Responsible Energy Development Act (REDA), SA 2012, c R-17.3 states that one of the Regulator’s mandates is to “provide for the efficient, safe, orderly and environmentally responsible development of energy resources in Alberta through the Regulator’s regulatory activities.”7 It is evident that the AER wants to be seen as excellent in meeting this goal. In 2014, it launched the a “best-in-class” project, seeking to identify the key attributes of an “excellent” regulator, adopt these attributes, and measure its progress by turning to researchers and community stakeholders.8 The AER sought out external expertise to establish baselines for its performance.

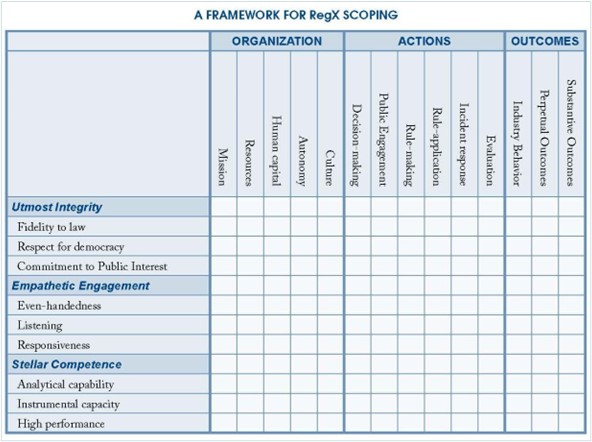

Published in 2015, the AER-commissioned, independently-written, and peer-reviewed “Listening Learning Leading: A Framework for Regulatory Excellence” report defines attributes of regulatory excellence (also referred to as “RegX”), lists strategies on how a regulator can become or remain excellent, and identifies normative measures for assessing regulatory excellence.9 It provides a general model for regulatory excellence and identifies three attributes that make up RegX: stellar competence, utmost integrity, and empathic engagement.10 Each element pairs a superlative adjective with a noun that speaks to excellence, indicating that true excellence demands top-tier efforts and outcomes. The report also identifies nine essential tenets of regulatory excellence that, if met, support a finding of strong RegX attributes. Refer to Figure 1 for the general framework for RegX scoping that includes the three attributes and nine tenets of regulatory excellence framed in terms of organization, actions, and outcomes.

Figure 1: Framework for RegX Scoping

Source: Cary Coglianese, “Listening Learning Leading: A Framework for Regulatory Excellence” (2015) Penn Program on Regulation (PPR), online (pdf): AER at x. [The framework appears to refer to “empathetic” rather than “empathic” engagement in error.]

After “Listening Learning Leading” was published, the AER made the general model for assessing regulatory excellence more Alberta-specific – as called for in the report – and engaged with Albertans, Indigenous peoples, stakeholders, and AER employees to provide feedback on how the AER measured up to the Alberta-specific model.11 The AER has stated that it is “committed to ensuring that regulatory excellence is reflected in everything [it does]” and that it will use the tailored RegX model to “achieve outcomes, continuously improve our performance, and measure our progress.”12 Given the AER sought out and upheld the RegX framework, it is germane to assess whether the AER’s regulation of inactive and orphaned wells met standards of excellence by considering the agreed-upon metrics of stellar competence, utmost integrity, and empathic engagement.

A. Utmost Integrity

The public rightly expects a regulator to have integrity: to be truthful and impartial. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines integrity as “the quality of being honest and fair” and REDA states that every AER director, hearing commissioner, and officer has a duty to “act honestly and in good faith” in carrying out their powers, duties and functions.13 Utmost integrity goes beyond a mere lack of corruption and extends to a regulator’s character.14 It speaks to a basic understanding of fairness, calling to mind the famous aphorism that “justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done.”15 For a regulator to be of utmost integrity, it must have durable inner virtues that are consistent and observable.

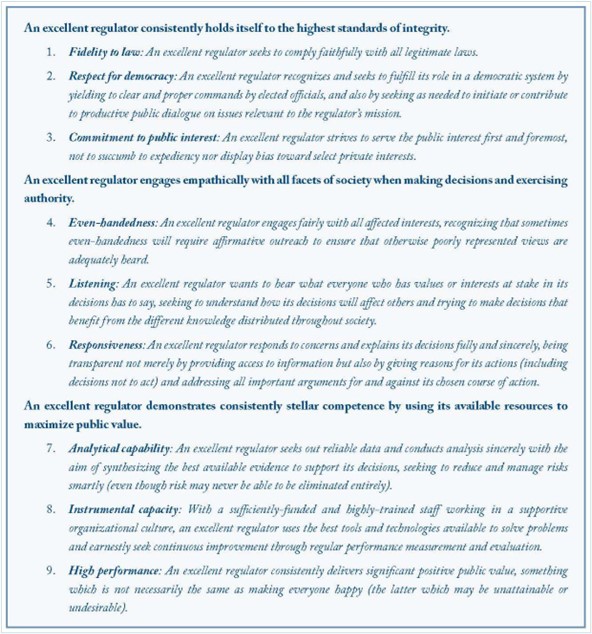

The “Listening Learning Leading” report notes the tenets of fidelity to law, respect for democracy, and commitment to public interest are aligned with utmost integrity (see Figure 2). An excellent regulator should possess all three tenets, and to do so indicates that it holds itself to the highest standards of integrity. Building on these tenets, the AER’s “Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence” publication finds the principles of accountability, adherence to government policy, identification of policy gaps, and evidence-based decision-making are those valued by the AER in discussing utmost integrity.16

Figure 2: Nine tenets of regulatory excellence and the three RegX models

Source: Cary Coglianese, “Listening Learning Leading: A Framework for Regulatory Excellence” (2015) Penn Program on Regulation (PPR), online (pdf): AER at 25.

The principles of accountability and evidence-based decision-making align closely with a commitment to public interest. A commitment to the public interest means that the regulator seeks to serve the public interest “first and foremost” and avoids over-prioritizing expediency or private interests.17 A regulator is accountable to the public, and it can demonstrate this tenet by regularly reporting on its actions and decisions. The AER specifies that accountability is not simply reporting successes or sharing data but also admitting mistakes and communicating frankly and clearly.18 A regulator that puts private interests before public interests, refuses to be transparent about its work and mistakes, and makes decisions based on anecdotal evidence does not meet the standard of integrity, much less utmost integrity.

The principle of adherence to Alberta government policy aligns with fidelity to the law. The AER’s work is guided by “legislation and government policy.”19 REDA establishes the AER as a corporation and, while it is not an agent of the Crown, it is a public agency under the Alberta Public Agencies Governance Act.20 It is subject to laws governing corporations and public agencies, and its fidelity to the law encompasses faithful compliance with all legitimate, applicable laws.21 Regulatory behaviours that would fail to demonstrate fidelity to the law could range from accepting kickbacks to failing to meet statutory obligations.

Identifying policy gaps also aligns closely with having a respect for democracy. For a regulator, respect for democracy balances yielding to legal commands by democratically-elected officials with identifying gaps in public policy that are relevant to its mandate.22 Despite a regulator’s rule-making being legally subsidiary to the Alberta legislature and government policymakers, it must carefully weigh stringency and flexibility when rule-making to better shape industry behaviour and deliver desired, substantive outcomes.23 A regulator that ignores clear commands by elected officials and fails to fill relevant intra vires policy gaps or raise relevant ultra vires policy gaps with the government would not meet the standard of respect for democracy.

B. Empathic Engagement

Empathic engagement relates to transparency and stakeholder management. The Alberta Public Agencies Governance Act preamble includes the line “WHEREAS clear communication and transparency are desirable with respect to the governance, mandates and activities of public agencies.”24 For a regulator, to engage empathically is to discourse with or consider all parties impacted by its decisions and exercise of authority. The “Listening Learning Leading” report notes that even-handedness, listening, and responsiveness align with empathic engagement (see Figure 2). The AER’s “Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence” publication provides that empathic engagement for the AER means respectful external and internal engagement, understandable decisions, and being transparent.25

Respectful engagement aligns closely with listening. The “Listening Learning Leading” report identifies this latter action in the first word of its title; a regulator should not work in siloed spaces and should understand its role within a community. Respectful engagement is to prioritize building strong relationships, seeking to understand values and concerns and engaging in information sharing.26 Choosing to engage with a select few stakeholders and to ignore or merely tolerate the rest would not constitute listening.

Transparency and decisions being understood align with responsiveness and even-handedness. These qualities are all grounded in communication between the regulator and its stakeholders. An excellent regulator understands when affirmative outreach is needed to ensure views that would be otherwise poorly represented are heard and provides reasons for and against its course of action.27 Failing to communicate reasons for decisions, hiding pertinent information from the public, and disregarding the experiences of marginalized groups would demonstrate poor responsiveness and even-handedness.

C. Stellar Competence

Stellar competence involves a high-level deployment of human and data resources. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines competency as “possession of sufficient knowledge or skill” but an excellent regulator must both possess competence and perform competently.28 The “Listening Learning Leading” report notes that analytical capability, instrumental capacity, and high performance align with stellar competence (see Figure 2). The AER’s “Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence” publication finds that, for it to achieve stellar competence, it would need to have the required expertise and tools, be able to adapt to new risks and opportunities and measure and report performance.29

Required expertise, tools, and measuring and reporting align closely with instrumental capacity. The latter attribute denotes adequately-funded and well-trained staff using the best tools and technologies available.30 The AER notes that having required expertise can mean obtaining outside expertise and measuring and reporting requires performance evaluation.31 A regulator with poorly-trained staff, outdated tools and technologies, and little performance measurement and evaluation would not meet the bar for instrumental capacity.

Adapting to new risks and opportunities aligns with analytical capability. To be analytically capable is to conduct analyses with reliable data and mitigate risks intelligently.32 It is a given that some risks cannot be entirely eliminated, but an excellent regulator has a risk-informed approach that requires identifying and managing risks and opportunities using data and analysis.33 A regulator that does not properly identify risks and opportunities and fails to use reliable data in its market analyses would not have strong analytical capability.

High performance encompasses all the aforementioned attributes; it is the result of instrumental capacity and analytical capability. An excellent regulator deploys its human and data resources to consistently create positive public value.34 If a regulator has strong instrumental capacity and analytical capability but fails to deliver value, it is not performing at a high level and should reconsider its strategies.

III. Understanding the scope of Alberta’s inactive and orphaned well crisis

A. Terminology

In characterizing the scope of Alberta’s inactive and orphaned well crisis, defining a number of terms will help ground the research. The definitions below are extracted from the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) and the Government of Alberta websites.35

An inactive well is a “well…where activities have stopped due to technical or economic reasons.”36 Inactive wells are differentiated from abandoned wells and can be reactivated.37 When considering whether to reactivate a well or proceed with abandonment, the well must be suspended according to the suspension requirements for inactive wells outlined in Directive 013 outlines.38 Based on AER data, there is a low likelihood of a well being reactivated if it has been inactive for more than two years.39

An abandoned well is a “site that is permanently dismantled (plugged, cut and capped) and left in a safe and secure condition.”40 Similarly, under the Oil and Gas Conservation Act, “abandonment” is, as it applies to non-pipeline matters, “the permanent dismantlement of a well or facility in the manner prescribed by the [Act’s] regulations or rules and includes any measures required to ensure that the well or facility is left in a permanently safe and secure condition.”41

Remediation and reclamation involve, respectively, “cleaning up a contaminated well site to meet specific soil and groundwater standards” and “replacing soil and re-establishing vegetation on a wellsite so it can support activities similar to those it could have supported before it was disturbed.”42

Lastly, an orphaned well is one “confirmed not to have anyone responsible or able to deal with its closure and reclamation.”43 End-of-life obligations include closure activities.

B. History of the inactive and orphaned well crisis

Alberta’s large inventory of inactive wells is a long-term issue with parallels in other jurisdictions. When the very purpose of an oil and gas well is to extract a limited resource, it can be expected that issues may arise when a well, and/or its owner or operator, “runs dry,” i.e. are no longer economically or functionally viable. A Google search of “abandoned44 wells in the United States” brings up varying articles about similar crises, a billion dollar mess, and contaminated groundwater and aquifers in California, Texas, and New Mexico. While the governments of Russia, Saudi Arabia, and China – who comprise top global oil and gas producers – seem reluctant to provide abandoned well data to hungry journalists,45 it is not outside the realm of imagination that they too may be grappling with the financial and/or environmental ramifications associated with inactive and, particularly, orphaned wells.

Early warnings and risks

As early as 1986, the AER’s predecessor, the Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB), identified the number of inactive wells in the province were rapidly increasing.46 Inactive wells pose great environmental and health risks as pollutants, like methane gas, can migrate from inactive wellbores to the surface, soil, groundwater, and aquifers, worsening climate change, financially burdening the government and taxpayers, and subjecting landowners to opportunity costs.47 Though properly abandoned wells pose less risks of leakage than improperly abandoned or inactive wells, such leaks are still possible and leakage risks have been historically underestimated.48

The Long Term Inactive Well Program

As of 1989, Alberta had over 25,000 inactive wells.49 Over the next two decades, Alberta’s energy regulator was reorganized and renamed, but all agency variants tried to reduce the risks resulting from increasing inactive wells in varying ways, from establishing an Abandonment Fund to manage abandoned orphan wells to introducing programs that required operators to abandon, operationalize, transfer, or pay an abandonment deposit for wells that had been inactive for more than 10 years.50 In 1997, the provincial energy regulator introduced the Long Term Inactive Well Program (LTIWP), which required operators to reduce the number of wells that had been inactive for more than 10 years by resuming production, abandoning the wells, paying a security deposit, or transferring the wells within a 5-year period.51 Nevertheless, the number of inactive wells in Alberta continued to grow.

The Licensed Liability Rating Program

The Alberta legislature passed the Energy Statutes Amendment Act, 2000, which replaced the Abandonment Fund with the Orphan Fund and expanded the fund’s scope of coverage to include suspension and reclamation.52 The provincial energy regulator then replaced the LTIWP program with the Licensed Liability Rating (LLR) Program, aiming to reduce the risk of wells being orphaned and the Orphan Fund’s correlating liability.53 Through the LLR Program, the regulator estimated this risk by requiring licensees who had a deemed assets to deemed liabilities ratio, so-called the Liability Management Rating (LMR), less than 1.0 to reduce their liabilities or post security deposits for end-of-life obligations.54 However, its calculations relied on industry netbacks and regional average costs, leading many high-risk companies to be deemed as having a liability ratio greater than or equal to 1.0.55 These overly simplified calculations created perverse incentives.56 For example, since inactive wells could be deemed positive assets, a licensee with a low LMR ratio was incentivized to amass such wells until they equalled their liabilities.57 The provincial energy regulator claimed it lacked the mandate and resources to evaluate the corporate health of its licensees.58

Despite early-identified issues, the provincial energy regulator waited until 2013 to modify the LMR calculation assumptions to better estimate deemed liabilities, phasing in higher deemed well abandonment and reclamation cost estimates.59 In 2014, the provincial energy regulator, now titled the AER, introduced the LLR Program Management Plan which allowed high-risk licensees to pay outstanding security amounts through quarterly payments if they, among other obligations, provided more specific financial information.60 In 2017, the AER adjusted the LMR formula again, collecting additional well information to better assess abandonment liability.61

Inactive Well Compliance Program

Introduced in 2014, the AER’s Inactive Well Compliance Program sought to bring all inactive, non-compliant wells into compliance with Directive 013.62 While the provincial energy regulator first published Directive 013 requiring inactive wells to be suspended within a particular time in 2004, 84% of all inactive wells in the province were non-compliant with the directive in 2015.63 The Inactive Well Compliance Program required licensees to bring 20% of non-compliant wells to compliance by reactivating, abandoning, or suspending them over a period of 5 years. As of 2019, inactive wells not in compliance with Directive 013 had fallen to 22%.64

Responding to the Liability Management Framework

In July 2020, the Government of Alberta introduced a new Liability Management Framework and amended the Oil and gas Conservation Rules, Alta Reg 151/1971 and Pipeline Regulation, Alta Reg 91/2005, setting policy direction and noting that the AER was responsible for administration.65

One component of the Framework includes replacing the AER’s current LLR program with an improved one that better assesses a licensee’s ability to meet regulatory liabilities obligations before receiving regulatory approval by assessing corporate health using a wider variety of parameters.66 The AER has responded with a draft directive that introduces the Licensee Management Program.67 Rather than doing a limited LMR calculation, the AER will now do a licensee capability assessment (LCA) that could take into account factors like financial health and rate of closure activities and “any other factor the AER considers appropriate as the LCA evolves.”68

The Liability Management Framework also empowers the AER to set closure quotas for inactive wells, to which the AER has responded by setting industry-wide targets and forecasts.69 As of 2022, each oil and gas licensee with inactive well liabilities will be required to meet an individual annual mandatory target determined by the AER and, “in lieu of meeting this [target] through closure work, the licensee may elect to provide a security deposit to the AER in the amount of the mandatory target.”70 Moreover, if the licensee fails to pay this security deposit, the AER will require an additional amount to compensate for the increased liability risk.71

Lastly, the Framework calls for a process to address legacy and post-closure sites and expands the mandate of the Orphan Well Association.72

As of July 2023, there were around 81,000 inactive wells that had not been abandoned or reclaimed and around 89,000 abandoned wells that had not been reclaimed in Alberta.73

Prior to the introduction of the Liability Management Framework, the AER privately projected the number of inactive wells to double to 180,000 by 2030.74 Only time will tell if the recent legislative and regulatory changes will counteract decades of unsuccessful programs and policies.

IV. Assessment of the AER’s regulation of inactive and orphaned wells using the tailored RegX framework

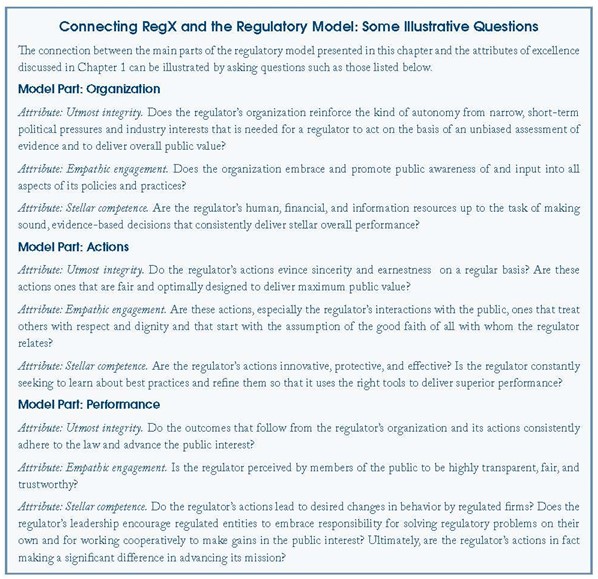

This section will analyze the AER’s regulation of inactive wells since 1986 using the tenets, principles, and examples of regulatory excellence identified in Part II and the illustrative questions in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Illustrative Questions for connecting 3 core regulatory attributes of excellence (RegX) with general model of a regulator’s organization, action, and performance.

Source: Cary Coglianese, “Listening Learning Leading: A Framework for Regulatory Excellence” (2015) Penn Program on Regulation (PPR), online (pdf): AER at 40.

A. Utmost Integrity

The AER’s failure to uphold the polluter pays principle challenges a claim to utmost integrity. In his 2021 and 2023 Reports, the Auditor General of Alberta stated that environmental legislation in Alberta is based on the “polluter pays principle” which holds that those responsible for pollution should clean it up and pay for it.75 The Alberta Energy Regulator’s website implies that it operates using similar logic, stating:

In Alberta, we live by a simple rule: if energy companies are going to profit from the province’s energy resources, they must be responsible and properly abandon, remediate, and reclaim their sites.76

Holding polluters accountable for their pollution demonstrates utmost integrity because doing so both serves the public interest and aligns with fidelity to the law. For three decades, the AER’s lax and incremental regulatory measures accelerated the ballooning of end-of-life liabilities to tens of billions of dollars, compelling government intervention at the federal and provincial level.77 The AER permitted a near-decade of non-compliance with the Directive 013 until it introduced the AER’s Inactive Well Compliance Program. By then, 84% of all inactive wells in the province were non-compliant with the directive. In waiting so long to act vigilantly on non-compliance with suspension requirements, the AER failed to collect mandated fees and galvanized increased environmental risks. There is a public interest component when oil well cleanup costs are estimated at billions and, as of January 2024, the Alberta Energy Regulator’s total LMR security held was about $316 million.78 Further still, prioritizing suspension rather than abandonment has environmental costs; suspended wells are more prone to gas leaks than abandoned wells, and such leaks release methane emissions.79 The costs of suspended, leaking wells include societal and environmental impacts.80 These are extranalities shouldered by society at-large. Internalizing these extranalities by acting faster to address non-compliance upholds the polluter pays principle and promotes fidelity to the law.

The AER has a “cradle-to-grave licensing regime”; in granting a drilling license, a licensee must assume end-of-life responsibilities in the form of abandonment, remediation, and reclamation.81 It is recognized that the AER may have phased its compliance measures, granted extensions, and assessed liabilities using broad criteria to protect an Albertan economy that relies so strongly on the oil and gas industry.82 Having a strong job market and profitable businesses serves the public interest. However, an excellent regulator is not a booster or rubber stamp for industry.83 A licensee must factor in its end-of-life responsibilities as it factors in its profits. Given the AER is completely industry-funded, it is at an increased risk of regulatory capture and increased transparency measures are all the more vital. An excellent regulator would not permit the oil and gas industry at-large to privatize their gains and socialize their losses.

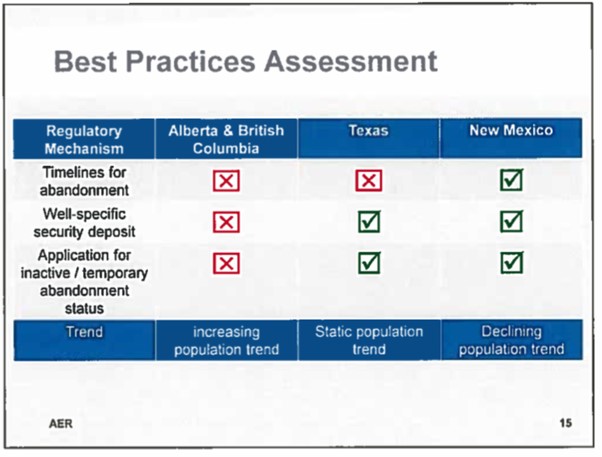

The AER declined to fill vital policy gaps within its jurisdiction. When concerns arose regarding its LMR calculation assumptions, it claimed to not have the mandate or resources to evaluate its licensees' corporate health and relied on voluntary surveys to collect data on abandonment and reclamation costs.84 When the government provided little incentive for licensees to abandon their wells, the AER did not impose a mandatory timeline on operators to meet their abandonment and reclamation obligations when it had imposed similar timelines for suspension with Directive 013 (see Figure 4). The AER could have acted sooner before the Inventory Reduction Program was introduced in this gap through the Liability Management Framework.

Figure 4: AER Presentation Comparing Liability Management

Source: Mike De Souza et al, “Alberta regulator privately estimates oilpatch's financial liabilities are hundreds of billions more than what it told the public” (2018), online: Canada’s National Observer.85

Ultimately, though the AER avoided potentially profit-stifling directives that may have hurt the immediate economic interests of the public, it failed to meet the high standard of utmost integrity by inconsistently applying the polluter pays principle and not addressing policy gaps through programs within its jurisdiction. As the oil and gas industry remains unstable and bankruptcies of AER licensees rise, it is likely that wells will be increasingly orphaned.86 If the industry is not adequately levied and held accountable, the costs may fall to the taxpayers. The AER’s new Licensee Management Program should set reasonable deadlines for specific overall liability reductions that factor in industry accountability. To be an excellent regulator, the AER should be more transparent about its past, current, and future mistakes and uphold the polluter pays principle.

B. Empathic Engagement

In managing Alberta’s inactive well issues, the AER did not engage empathically with all relevant stakeholders when making decisions and exercising authority.

The AER variably communicated the magnitude of the liability obligations owed by licensees. In 2018, it knew that its verified calculations of $58.65 billion for total liabilities could be $260 billion in a hypothetical, but unvalidated, worst-case scenario.87 When the latter amount was leaked to the press, the AER noted that it was brought up in a presentation to industry to stress that its current liability system needed improvement.88 It felt obliged to share this information with private parties, but not the public at large.89 This point begs the question: By 2018, did the LLR Program need improvement, as the AER attempted through incremental changes, or did it need restructuring? Did the public-at-large understand why the AER had not yet overhauled the program as its predecessors did with numerous programs in the past? The AER did not and has not clearly articulated the reasons for its decision not to act sooner.90

The AER has non-industry stakeholders whose views seem to have had little application in its decision-making. Academics and journalists have advocated for alternative methods to incentivize abandonment for decades.91 The AER has a history of reverting strong regulatory measures amid industry backlash and introducing weak regulatory measures that are marginally improved despite major issues being present.92 Its inactive well list also appears to be industry-facing, reducing transparency. However, the AER does have a Stakeholder Engagement Framework and Multi-Stakeholder Engagement Advisory Committee, solicit the opinions of the public, and regularly publish directives and bulletins, dating back to 1978.93 With the draft Licensee Management Program, Albertans will have the opportunity to engage with the AER’s potential directive changes through a public feedback process.94

The AER is moderately engaging, but not at the standard of empathic engagement. The AER has demonstrated a heightened engagement with the industry but, as a regulator, this is not indicative of listeningto the public. Engaging more meaningfully with marginalized viewpoints, particularly those critical of the its work, may constitute stronger empathic engagement. The AER could also provide more reasons for its assertions, for example, why requiring more specific financial information from licensees prior to the Liability Management Framework fell outside of its mandate.

C. Stellar Competence

The AER has not demonstrated stellar competence in addressing the issue of inactive wells, because it did not consistently use its available resources to maximize public value.

Aware of growing liabilities, the AER failed to implement many of the risk mitigation strategies seen in other jurisdictions (see Figure 4). It did not direct any timelines for abandonment or call for well-specific securities, despite knowing these strategies could reduce end-of-life liabilities (see Figure 4). It chose to remain focused on encouraging suspension through Directive 013, rather than abandonment and reclamation.95 In doing so, it poorly regulated against – if not did not regulate against – the increasing number of inactive, unabandoned wells. One may argue that abandonment need not be a priority when some licensees may be aiming to reactivate wells. However, the AER’s own data tells a different story: the AER has found that inactive wells have been reactivated less than 0.2 percent of the time.96 According to a 2017 briefing paper written by Professor Lucija Muehlenbachs, the number of inactive wells in Alberta would reduce by, at most, 12% in twelve years assuming an astronomically-high oil price of $197.72 per barrel of oil, a 100 percent recovery rate, or reactivation costs dropping by 25 percent.97 Setting aside this study occurring in 2017, duplicating such circumstances in 2023 would result in about 71,280 wells still left inactive (81,000 inactive wells in 2023 x (1.00-0.12)) in 2035.98 Even in ideal circumstances, the AER’s approach, and particularly its focus on well suspension, would only marginally reduce the number of inactive wells. A policy that permits the indefinite suspension of oil wells incentivizes AER licensees to suspend, rather than abandon, oil wells – not because of the option to reactivate, but rather due to the high sunk costs of abandonment.99 An excellent regulator would appreciate this reality and synthesize the best available data to support its aims to reduce the number of inactive wells.

Lastly, the regulator did not collect sufficient financial information from its licensees, demonstrating a lack of instrumental capacity. While there may be privacy and information management issues at play, the AER’s approach to assessing the financial health of its licensees appears to be lacking, given financially-troubled companies could strategically accrue negative value assets to avoid paying securities. Many of the laws governing closure liability and the programs administered by the AER in Alberta are broadly discretionary.100 As noted above, through the LLR Program Management Plan, the AER required more specific forecast revenues and operating costs from companies it deemed high-risk.101 To require this from all licensees appears to have been within the AER’s mandate. The AER is likely to have had the required expertise and tools to understand that the LMR calculations were made with limited assumptions that could distort risk assessments and create perverse incentives.

Alberta’s energy sector is “vast and complex”; the AER regulates licensees in a multifaceted, variable environment.102 For example, the 2014 Alberta oil crash was estimated to be a short-term downturn but was, rather, unprecedented and long-term.103 However, while the AER was operating within this uncertain space, it should have adjusted its calculations and expectations as an excellent regulator would. Instead, it pushed forth with unsupported optimism as if it were operating in ideal circumstances. Many of the AER’s regulatory decisions, in the context of inactive oil wells, have been rooted in poor mathematical assumptions and risk assessments.104 The AER’s poor instrumental capacity and analytical capability is reflected in its inability to adequately identify and hold accountable high-risk licensees and the increasing number of inactive wells amid a stagnated number of well abandonments.105 The AER’s regulatory management has exacerbated liabilities that were already increasing prior to the 2014 Alberta oil crash. The AER does not meet the standards of stellar competence, and should rightly be reconsidering its strategies, as it is now doing.

D. Does the AER’s regulation of inactive and orphaned wells meet the standards of regulatory excellence?

Given the standards of regulatory excellence require an abundance in possession, and consistent demonstration, of RegX attributes, it is evident that the AER is not an excellent regulator. Alberta’s energy regulator recognized that its licensees’ increasing number of inactive wells posed significant risks as early as 1986 but failed to tamper this issue in meaningful ways over the past three decades. In inconsistently applying its authority, it did not adequately uphold its cradle-to-grave licensing regime regime. It must also be noted that, grounding all of this analysis, is a provincial government that has introduced ineffective statutory and policy changes and also contributed to exacerbating the inactive and orphaned well crisis.106

It is likely that few regulators truly meet the high bar of regulatory excellence stipulated in the “Listening Learning Leading” report. Principally, it is a more productive exercise to assess one’s progress in relation to the standards rather than determining whether the standards were met at all. The “Listening Learning Leading” report quotes American football coach Vince Lombardi, who reportedly once said that “if we chase perfection, we can catch excellence.”107 Hence, regulatory excellence is like the “summit of a mountain.”108 It is difficult to reach, but there are many paths and difficulty alone should not deter a regulator from aiming for the top.

V. Conclusion

This is a modest contribution to the literature on regulatory excellence and the AER’s regulatory capability. More research is needed to fully encapsulate the issues at hand, particularly amid a transitioning liability management system. This paper does not evaluate the proposed Liability Management Framework and largely focuses on the AER’s regulatory management of inactive wells prior to the Framework’s introduction. Ultimately, the AER’s approaches to inactive well management are indicia of poor regulatory practices and do not meet the standards of regulatory excellence. That is not to say that the AER is a poor regulator; its approaches may differ across all its tasks and this report has focused on one mandate of many.

With the new Liability Management Framework delegated from above and quickly moving regulatory action, Albertans should watch the AER with scrutinous eyes. Reimagining Alberta’s liability management system was long overdue, but it still ought to be done excellently.

Endnotes

1 See Vanessa Alboiu & Tony R Walker, “

Pollution, management, and mitigation of idle and orphaned oil and gas wells in Alberta, Canada”, (2019) 191:10 Environmental monitoring and assessment, Springer 610 [Vanessa Alboiu & Tony R Walker] at 612; Clayton Aldern, Christopher Collins, & Naveena Sadasivam, “

Waves of Abandonment, The Permian Basin is ground zero for a billion-dollar surge of zombie oil wells”,

Grist (March/April 2021) [

Grist] (Scatter plot created with Texas, New Mexico, and federal data illustrates that annual rates of well abandonment rise with falling oil prices in the United States).

3 Oil and Gas Conservation Act, RSA 2000, c O-6. See s 1(1)(fff) (The Act defines “working interest participant” as “a person who owns a beneficial or legal undivided interest in a well or facility under agreements that pertain to the ownership of that well or facility”) and Part 11 (The Act sets out the purpose and scope of the orphan fund).

4 Ibid at ss 70(1)(b), 71(2).

6 See

Alberta Energy Regulator, Public Statement, PS2018-5, (1 November 2018) [PS2018-5] (The AER stated that its estimated $260 billion in total liability was “based on a hypothetical worst-case scenario” and created for a presentation to “try and hammer home the message to industry that the current liability system needs improvement”);

Boychuk et al, “The Big Cleanup How enforcing the Polluter Pay principle can unlock Alberta’s next great jobs boom”, “Alberta Liabilities Disclosure Project” (June 2021);

Alberta Liabilities Disclosure Project, Press Release, (29 June 2021) (Identifies subsidies and AER securities as against industry liabilities);

Fenner L Stewart & Scott A Carrière, “Natural Resource Disputes and The Federal State” in Trevor Tombe & Jennifer Winter, eds, “Measuring the Contribution of Energy Infrastructure: A Practical Guide” (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2020) (Notes that the 2014 Oil Crash resulted in a “tidal wave of bankruptcies” in the oil and gas industry amid $58 billion in outstanding end of life obligations);

Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski, “A Made-in-Alberta Failure: Unfunded Oil and Gas Closure Liability” (2023) 16:1 University of Calgary School of Public Policy [Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski] at 6-9, 11 (See also for a comprehensive evaluation of the Alberta Liability Management Framework).

9 “Listening Learning Leading”,

supra note 8 at i (The report was informed by dialogue sessions, two of which took place in Alberta, involving over 150 expert and industry participants, leading global experts, and high-level regulators in Washington, DC).

10 Ibid at 40 (The report conceptually groups the following three core attributes in a so-called “RegX” molecule, characterizing regulatory excellence as a 3-component, synergetic cluster).

11 Alberta Energy Regulator, “

The Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence”, (April 2016) at 1 [“Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence”].

Ibid at 4 (“Although the Best-in-Class Project was the brainchild of the AER’s leadership, this report’s framework of regulatory excellence has been from the start expressly intended to be general enough to be used by any regulator around the world, in any area of regulation. …This Final Report, though, is not a simple cookbook for the AER or any regulator”).

14 “Listening Learning Leading”,

supra 8 at 23.

16 “Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence”,

supra note 11 at 2 (“Utmost integrity means that we are ‘accountable’ as a protective, effective, efficient, and credible energy regulator that is fair and unbiased. We ‘adhere to Alberta government policy’ and take a leadership role in ‘identifying policy gaps’ where they exist. We make ‘evidence-based decisions’ that consider the environment, the unique nature of the energy development, traditional knowledge, and information brought forward by local communities” [emphasis added]).

17 “Listening Learning Leading”,

supra note 8 at iii.

18 “Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence”,

supra note 11 at 2.

21 “Listening Learning Leading”, supra note 8 at iii.

25 “Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence”,

supra note 11 at 4 (“We are committed to ‘respectful external and internal engagement’. For us, empathic engagement means working together so that we can make fully informed decisions and build strong relationships. We are straightforward about the issues, listen carefully, respond respectfully, and ensure that our ‘decisions are understood’. We know that to build and maintain relationships we must be fair, inclusive, and ‘transparent’” [emphasis added]).

26 “Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence”, supra note 11 at 4.

27 “Listening Learning Leading”, supra note 8 at iii.

29 “Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence”,

supra note 11 at 3 (“Stellar competence means our people have the ‘required expertise’ and necessary ‘tools’ to carry out their responsibilities, which underpins our ability to achieve outcomes while ‘adapting to new risks and opportunities’. We will seek expertise and information outside of our organization to make well-informed decisions. This is how we deliver outcomes, ‘measure and report’ on our performance, and continuously improve.” [emphasis added]).

30 “Listening Learning Leading”,

supra note 8 at iii.

31 “Alberta Model for Regulatory Excellence”,

supra note 11 at 3.

32 “Listening Learning Leading”,

supra note 8 at iii.

36 Oil and gas liabilities management,

supra note 35 (The definition further states that “ Not all sites in this category are orphaned. Many may be reopened and produce again at a later date”). See also

Alberta Energy Regulator, “Directive 013: Suspension Requirements for Wells” (Calgary: AER, 2022) [

Directive 013] at s 1 (According to AER

Directive 013, inactive wells are either “critical sour wells (perforated or not) that have not reported any type of volumetric activity (production, injection, or disposal) for six consecutive months” or “all other wells that have not reported any type of volumetric activity (production, injection, or disposal) for 12 consecutive months”).

37 See Oil and gas liabilities management,

supra note 35 (The well inventory listed distinguishes inactive wells from abandoned wells).

38 Directive 013,

supra note 36 at s 2.

40 Oil and gas liabilities management,

supra note 35.

42 Oil and gas liabilities management,

supra note 35.

44 In the United States, the terms ‘abandoned,’ ‘idle,’ and ‘orphaned’ are often interchangeably used to describe a well that did not locate marginally economic hydrocarbons or is at the end of its production lifecycle. Nevertheless, different jurisdictions have distinct criteria for what qualifies as an abandoned or orphaned well. See Richard J. Davies

et al, “

Oil and gas wells and their integrity: Implications for shale and unconventional resource exploitation” (2014) 56 Marine and Petroleum Geology 239 [Oil and gas wells and their integrity]. See also Memorandum from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “

Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks 1990-2016: Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells” (April 2018) (This United States Environmental Protection Agency memo describes abandoned wells as those with: “no recent production, and not plugged [with] common terms (such as those used in state databases) [that] might include: inactive, temporarily abandoned, shut-in, dormant, idle”; “no recent production and no responsible operator. [with] common terms might include: orphaned, deserted, long-term idle, abandoned”; “those [that] have been plugged to prevent migration of gas or fluids”).

45 See Nichola Groom, “

Special Report: Millions of abandoned oil wells are leaking methane, a climate menace” (June 2020) (The article notes that the governments of Russia, Saudi Arabia, and China both did not respond to Reuters’ requests for comment on their abandoned wells and have not published reports on the wells’ methane leakage). I appreciate that the response to this singular article does not represent responses to all other similar articles and does not indicate that the aforementioned countries have similar financial and environmental issues associated with inactive wells as Canada and the US.

49 Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 3; J. M. Abboud, T. L. Watson, & M. C. Ryan, “

Fugitive methane gas migration around Alberta’s petroleum wells” (2021) 11:1 Greenhouse Gases: Science and Technology 37 at 41 [“Fugitive methane gas migration around Alberta’s petroleum wells”]; Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski,

supra note 6 at 3.

50 See Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 3; Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski,

supra note 6 at 3-4.

51 See Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 3.

53 See Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 5.

55 Ibid at 6 (Robinson examines a company in clear and dire financial circumstances, operating at a net loss, and facing million-dollar lawsuits from a working interest partner. In 2013, the company’s LMR ratio was 1.48 despite years of financial trouble as early as 2008. The regulator did not require a security deposit from this company); Fenner L Stewart, “Environmental Liabilities, Governance Constraints, and The Public Interest: A Policy Story of Alberta’s $58 Billion Problem” (2020) [unpublished] at 35-36 [Stewart].

56 Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski,

supra note 6 at 18.

57 Stewart,

supra note 55 at 36.

58 Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 6 (Robinson notes that, in response to concerns, the provincial energy regulator stated that it does “not have the mandate or resources to evaluate the corporate health of companies holding licenses for upstream oil and gas activities in Alberta.”)

59 Stewart,

supra note 55 at 36.

60 Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 8 (This information did not include full income statements or actual liabilities but did include specific forecast revenues and operating costs).

65 “Liability Management Framework”,

supra note 2 at 1; Alberta Energy Regulator, “Bulletin 2020-26”, (December 17 2020).

66 “Liability Management Framework”,

supra note 2 at 1-2.

68 Ibid at 3 (Other potential assessment factors include estimated total magnitude of liability, rate of closure activities, spending and pace of inactive liability growth, and compliance with administrative regulatory requirements, including the management of debts, fees, and levies when assessing risks).

69 Ibid at 3 (The AER has set industry-wide targets of $422 million for 2022, $443 million for 2023, and forecasted targets for 2024-2026).

70 Alberta Energy Regulator, “

Bulletin 2021-23”, (June 8 2021) [AER Bulletin 2021-23].

Ibid at 1.

73 Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski,

supra note 6 at 1; Auditor General of Alberta 2023 Report,

supra note 39 at 27-28.

75 Alberta, Auditor General of Alberta, “

Report of the Auditor General” (June 2021) at 5; Auditor General of Alberta 2023 Report,

supra note 39 at 1, 10, 12.

77 See Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski,

supra note 6 at 7 (The authors reference the 2020 federal $1 billion grant to Alberta in exchange for a commitment by Alberta to make regulatory changes to better enforce the polluter pays principle); Stewart,

supra note 55 at 7-9 (Stewart questions who would lend money to an entity with no financial resources of its own, no ability to generate revenue on its own, and little legal obligation to repay); Geoffrey Morgan, “

AER lays off dozens of senior staff as board and Alberta government review embattled regulator”, Financial Post (January 22 2020) (In 2019, the Government of Alberta ousted AER’s board amid allegations of gross mismanagement of public resources). Note also: Taxpayers funding cleanup costs that should, at least in theory, be born by polluters is not unique to Canada. For example, in April 2021, United States Senators Ben Ray Luján and Kevin Cramer introduced a bipartisan Bill to establish a program and provide federal funds for the remediation and reclamation of orphaned oil and gas wells and surrounding lands. See S.1076 – REGROW Act of 2021, 1

st Sess, 117

th CONGRESS, United States, 2021 (This Bill also inspired a companion bill, H.R. 3585, in the United States House of Representatives).

83 “Listening Learning Leading”,

supra 8 at 55.

84 Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 6. I have failed to identify legislation prohibiting the AER from gathering detailed financial information from licensees that would have better assisted it in calculating liability.

85 This photo in Figure 4 was included in the National Observer article cited above with the caption: “A slide from a presentation on Feb. 28, 2018 by Alberta Energy Regulator vice-president Robert Wadsworth compares the management of liabilities in different jurisdictions. Screenshot from AER presentation.”

86 Stewart,

supra note 55 at 18.

87 See PS2018-5,

supra note 6 at 1.

90 “Listening Learning Leading”,

supra 8 at 25.

91 See Benjamin Dachis, Blake Shaffer & Vincent Thivierge, “

All’s Well that Ends Well: Addressing End-of-Life Liabilities for Oil and Gas Wells” (28 Sept 2017) C.D. Howe Institute Commentary 492 at 17; Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 14-22; Mark Polet, “

Energy And The Reclamation And Remediation Challenge In Alberta, Canada,” “Energy Management and the Environment: Challenges and the Future” ed by Anshuman Khare & Joel Nodelman (2007) at 224-225 (Suggests increased industry levies, risk management system); Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski,

supra note 6 at 6.

92 See J. M. Abboud, T. L. Watson, & M. C. Ryan, “

Fugitive methane gas migration around Alberta’s petroleum wells” (2021) 11:1 Greenhouse Gases: Science and Technology 37 (Article notes that the AER’s Long Term Inactive Well (LTIW) program was met with industry pushback and soon replaced, capitulating to industry interests); Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 11 (Robinson believes the 1997 LTIW program had the potential to “eliminate the backlog of long term inactive wells by 2002”).

95 As discussed, while companies may have abandoned and reclaimed inactive wells to avoid costs associated with failure to meet suspension requirements, the AER’s data demonstrated that, nearly a decade after Directive 013 was published, 84% of all inactive wells in the province were not in compliance with suspension requirements much less abandonment requirements. See Barry Robinson,

supra note 46 at 7; Alberta Energy Regulator, Public Statement, “

Year Three and Four Final Report In addition to Bulletin 2014-19, Alberta Energy Regulator (AER)”, (January 2020); Stewart,

supra note 55 at 30.

97 See Lucija Muehlenbachs,

supra note 82 at 7-8.

98 This calculation is a 2023 iteration of the analysis done in Fenner Stewart’s “Environmental Liabilities, Governance Constraints, and The Public Interest: A Policy Story of Alberta’s $58 Billion Problem” paper. See Stewart,

supra note 55 at 33.

99 Lucija Muehlenbachs,

supra note 82 at 11; Daniel Schiffner, Maik Kecinski, & Sandeep Mohapatra,

supra note 79 at 14-15.

100 Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski,

supra note 6 at 7-8 (“As one rough measure of the extent of this delegated discretion, the term “may” (e.g., the Regulator

may prescribe conditions) appears 190 times in the

Oil and Gas Conservation Act, 84 times in the

Pipeline Act and an astounding 437 times in the

Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act”).

102 Alberta Energy Regulator, “

Protecting What Matters” (This webpage includes the statement: “Alberta’s energy sector is vast and complex; it’s our job to make sure companies develop oil, natural gas, oil sands, and coal resources responsibly. We work hard to protect public safety and the environment, and to ensure that anyone with concerns about development can have their voice heard”).

103 Stewart,

supra note 55 at at 14-15.

104 See Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, & Martin Olszynski,

supra note 6 at 17-18.

105 Auditor General of Alberta 2023 Report,

supra note 39 at 27 (“While inactive well sites have grown, abandonment work has remained flat, and licensees have focused more on low-risk and lower-cost sites”).

107 “Listening Learning Leading”,

supra note 8 at 4.