April 14, 2025

Trevor McGowan

Associate Assistant Deputy Minister

Tax Policy Branch, Department of Finance Canada

90 Elgin Street, Ottawa, ON K1A 0G5

Dear Mr. McGowan:

Subject: Summary of Feedback on Various Technical Issues

This submission sets out comments of the Joint Committee on Taxation of the Canadian Bar Association and Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (“Joint Committee”) in respect of various technical issues. This submission is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all outstanding technical issues, but represents a consolidation of various issues which have been raised in discussions.

Members of the Joint Committee executive group and others in the tax community participated in the discussion concerning this submission and contributed to its preparation, including:

- Byron Scott Beswick – KPMG LLP

- David Bunn – Deloitte

- Ryan Minor – CPA Canada

- Carrie Smit – Goodmans LLP

- Anu Nijhawan – Bennett Jones LLP

- Jeffrey Shafer – Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP

We also would like to thank the members of the EIFEL working group for their valuable feedback and contributions to this submission.

Thank you for your consideration of this submission. If it would be helpful, members of the Joint Committee would be pleased to discuss the issues in more detail.

Yours truly,

Byron Beswick

Chair, Taxation Committee

Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada

Carrie Smit

Chair, Taxation Section

Canadian Bar Association

Cc: Robert Demeter, Director General, Tax Legislation Division, Department of Finance Canada

Summary of Technical Issues

1. EIFEL

Practitioners have identified the following technical issues under the Excessive Interest and Financing Expenses Limitation (EIFEL) rules. Future submissions may be made as additional issues are identified.

Section 78

Section 78 provides that where an amount in respect of a deductible outlay or expense is owing by a taxpayer to a non-arm’s length person, and that amount is unpaid at the end of the second taxation year following the year in which the outlay or expense was incurred, the amount is to be included in computing the taxpayer’s income in the third taxation year (assuming an agreement under paragraph 78(1)(b) is not filed). This income inclusion effectively offsets the deduction claimed in the year in which the amount was deducted. Where the outlay or expense was interest payable by a taxpayer subject to the EIFEL rules such that the interest was characterized as an “interest and financing expense” (IFE), the amount included in income under paragraph 78(1)(a) should be included in the taxpayer’s “interest and financing revenues” (IFR). Although IFR includes “an amount received or receivable as, on account of, in lieu of payment or in satisfaction of, interest”, it is not presently clear that an amount included in income under paragraph 78(1)(a) would be an IFR.

Recommendation: Variable A of the definition of “interest and financing revenues” in subsection 18.2(1) should be amended to explicitly include amounts which are included in a taxpayer’s income pursuant to paragraph 78(1)(a) where the corresponding outlay or expense was previously included in the taxpayer’s “interest and financing expenses”.

RIFE and Section 80

Paragraph 80(2)(b) provides that interest payable by a debtor in respect of an obligation issued by that debtor is deemed to be an obligation issued by the debtor having a principal amount equal to the amount of the interest that was deductible or would, but for subsection 18(2) or (3.1) or section 21, have been deductible in computing the debtor’s income. While the definition of a “commercial debt obligation” in subsection 80(1) was amended to include a debt obligation where interest would have been deductible but for subsection 18.2(2), a corresponding amendment to paragraph 80(2)(b) was not made to include interest that would be deductible but for subsection 18.2(2). As a result, interest which is not deductible under the EIFEL rules is not deemed under paragraph 80(2)(b) to be an obligation issued by the debtor, with the result that section 80 does not apply to the settlement of such interest. In such circumstances, it is possible that section 143.4 could apply to the debtor where there is a right to reduce such interest in a subsequent year, which would result in an income inclusion to the debtor under subparagraph 12(1)(x)(i).1

In addition, a forgiven amount under section 80 does not currently apply to reduce the taxpayer’s “restricted interest and financing expenses” (RIFE) under subsection 111(8).

From a policy perspective, the settlement of interest (which was not deductible under subsection 18.2(2)) should be subject to section 80 (not section 143.4), and any settlement of interest which is deemed to be an obligation under paragraph 80(2)(b) should be applied to reduce the RIFE of the taxpayer.

Recommendation: Paragraph 80(2)(b) should be amended to include interest which would, but for subsection 18.2(2), be deductible in computing the taxpayer’s income. Further, section 80 and the definition of RIFE in subsection 111(8) should be amended to provide that the settlement of interest which is deemed to be an obligation under paragraph 80(2)(b) should first reduce the taxpayer’s RIFE to the extent that the amount paid in settlement of such interest is less than the amount of interest owing.

“Excluded Entity” and “Eligible Group Entity”

Budget 2021, which announced that Canada would implement the EIFEL rules, included relief for “small businesses and for other situations that do not represent significant base erosion risks”2. This was implemented by exempting an “excluded entity” from the EIFEL rules. However, the definition of “excluded entity” is inappropriately restrictive in a number of situations. Certain examples are below.

Eligible Group Entity – Related and Affiliated

Paragraphs (b) and (c) of the definition of “excluded entity” in subsection 18.2(1) take into consideration the IFE, IFR, business activities, foreign affiliate shareholdings and shareholders of every “eligible group entity” in respect of the taxpayer.

The definition of “eligible group entity” in subsection 18.2(1) in respect of a taxpayer includes a corporation or a trust resident in Canada that is, at that time, related to (other than because of a right referred to in paragraph 251(5)(b)) or affiliated with (if section 251.1 were read without reference to the definition of controlled in subsection 251.1(3)) the taxpayer. Subsection 251(2) defines persons related to each other to include individuals who are connected by blood relationship, marriage or adoption3. Accordingly, the number of eligible group entities in respect of a taxpayer may be substantial and could include entities with no economic relationship with the taxpayer, as well as entities of which the taxpayer is unaware. For example, a corporation controlled by an individual would need to consider, not only other corporations controlled, directly or indirectly, by that individual but also corporations controlled by persons who are related or affiliated to that individual such as siblings and spouses of parents or children.

By including all related and affiliated persons (subject to limited exceptions), the exclusions from EIFEL that include references to eligible group entities are often impractical, as taxpayers may be unable to identify all related and affiliated corporations and trusts, determine the IFE, IFR, foreign affiliates and shareholdings in respect of related or affiliated entities and/or determine whether all or substantially all of the businesses, undertakings and activities of these related or affiliated entities were carried on in Canada.

In contrast to multi-national entities, where the related or affiliated rules encompass the corporate group, Canadian businesses owned by individuals often have a large network of related parties. Instead of narrowing the scope of the rules for Canadian businesses and family trusts, the use of affiliated and related parties within “eligible group entity” expands the scope well beyond the general purpose of the EIFEL rules.

Recommendation: The definition of “eligible group entity” should be amended to limit the number of corporations and trusts considered to be eligible group entities in respect of corporations and trusts owned by individuals. For example, paragraph (a) of the definition could be amended to replace “related” with “associated”. Alternatively, section 18.2 could be amended to add an interpretative rule providing that siblings, parents and adult children of an individual are not considered to be related to the individual for purposes of the definition of “eligible group entity”.

Categories of Excluded Entity

A corporate taxpayer may meet the test set out in paragraph (a) of the definition of “excluded entity” which is based on the quantum of its taxable capital. However, paragraph (a) only applies to corporations, such that trusts must rely on one of the other two paragraphs. Even where a corporation meets the test in paragraph (a), if the corporation is an “eligible group entity” in respect of a trust, the corporation and the trust must each meet one of paragraph (b) or (c) in order for the trust to be an “excluded entity”. This is inconsistent with the purpose of the excluded entity carve-out.

Recommendation: The definition of “excluded entity” in subsection 18.2(1) should be amended such that eligible group entities referenced in paragraphs (b) and (c) exclude eligible group entities which are excluded entities under paragraph (a) of the definition.

Partnerships

Issues under the “excluded entity” definition can also arise where a taxpayer is a de minimis/passive investor in a partnership. In order to determine whether a taxpayer is an “excluded entity” the taxpayer must ascertain the taxable capital, net IFE and Canadian operations of those investee partnerships, not all of which may file a partnership return (T5013) or agree to provide such detailed information.

Recommendation: The definition of “excluded entity” in subsection 18.2(1) should exclude, from the determination, certain partnerships where the taxpayer is a de minimis investor.

Tax-Indifferent Investors

Paragraph (c) of the definition of “excluded entity” includes a taxpayer resident in Canada which meets certain criteria, including that all or substantially all of the IFE of the taxpayer and each eligible group entity in respect of the taxpayer are paid or payable to persons or partnerships that are not “tax-indifferent” persons or partnerships that do not deal at arm’s length with the particular taxpayer or any eligible group entity in respect of the taxpayer.

“Tax-indifferent” is defined in subsection 18.2(1) to mean a person or partnership that is (a) exempt from tax under section 149; (b) a non-resident person; (c) a partnership more than 50% of the fair market value of all interests in which can reasonably be considered to be held, directly or indirectly through one or more trusts or partnerships, by any combination of persons described in (a) or (b); or (d) a trust resident in Canada if more than 50% of the fair market value of all interests as beneficiaries under the trust can reasonably be considered to be held, directly or indirectly through one or more trusts or partnerships, by any combination of persons described in (a) or (b).

It is challenging for publicly traded mutual fund trusts, including real estate investment trusts (REITs), to determine whether they satisfy paragraph (d) of the definition of “tax-indifferent.” While safe-guards are typically in place to ensure that non-resident investors are limited4, mutual fund trusts are typically widely held collective investment vehicles, often held in street name (e.g., a mutual fund dealer or registered securities dealer holding the units as nominee for the beneficial owner). As a result, a publicly traded mutual fund trust such as a REIT may receive interest from a non-arm’s length payor, such as a captive subsidiary of the mutual fund trust, but be unable to assess whether more than 50% of its units are held by a combination of non-resident or tax-exempt persons, thereby making it unable to determine if the mutual fund trust qualifies as tax-indifferent. As a result, eligible group entities may be excluded from qualifying as excluded entities and could be subject to EIFEL restrictions. From a policy perspective, we understand the EIFEL rules were not intended to apply to purely Canadian structures that would otherwise meet the excluded entity definition, but for intercompany debt.

Recommendation: The definition of “tax-indifferent” in subsection 18.2(1) should be amended to exclude mutual fund trusts which themselves would otherwise constitute excluded entities.

Upstream Loans / Excess Capacity

When a foreign affiliate (FA) makes an upstream loan to its Canadian corporate shareholder, and the interest on such loan is subject to Canadian withholding tax, the IFR definition ensures that the deduction for the taxpayer under subsection 91(4) with respect to Canadian withholding tax suffered by the FA does not reduce the amount added to the taxpayer’s IFR with respect to the underlying interest income. In particular, variable G of the IFR definition includes a reduction for an amount deducted under subsection 91(4) other than any portion of the amount that is in respect of income tax paid under subsection 212(1). Accordingly, if Canco owns an FA, and the FA makes an upstream loan to Canco the interest on which is subject to withholding tax under subsection 212(1), the gross interest income earned by the FA will give rise to an IFR inclusion for Canco, which allows the IFE incurred by Canco to be deducted without an EIFEL restriction.

From a policy standpoint, the same should be true if the FA makes a loan to a related Canadian corporation other than the direct Canadian corporate shareholder. For example, if Canco1 owns Canco2 which owns an FA, and the FA makes an upstream loan to Canco1 the interest on which is subject to a 25% withholding under subsection 212(1), one would expect Canco2 to have “excess capacity” equal to the underlying interest income earned by the FA, which would then be available to transfer to Canco1 to support the deduction of its IFE. However, there appears to be an unintended anomaly in the “excess capacity” definition that results in a 30% reduction to the IFR of Canco2, such that only 70% of the IFE incurred by Canco1 can be supported.

In particular, under variable F of the “excess capacity” definition, the amount included with respect to IFR is based on the following formula:

G – H x I

where

G is the IFR of the taxpayer for the year,

H is the ratio of permissible expenses of the taxpayer for the year (i.e., 30%), and

I is the lesser of (i) the amount by which the IFR of the taxpayer for the year exceeds the IFE of the taxpayer for the year, and (ii) either (A) if the ATI of the taxpayer for the year would, in the absence of section 257, be a negative amount, the absolute value of the negative amount, or (B) in any other case, nil.

In the above example, where Canco1 owns Canco2 which owns an FA, and the FA makes an upstream loan to Canco1 the interest on which is subject to a 25% withholding tax under subsection 212(1), the formula would work as follows (assuming there is $100 of interest and Canco2 is a pure holding company with no other sources of ATI or IFE/IFR):

G – H x I

where

G = the taxpayer’s IFR for the year, being $100.

H = the ratio of permissible expenses for the year, 30%, and

I = the lesser of (i) IFR > IFE for the year, being $100, and (ii) the absolute value of the taxpayer’s negative ATI for the year, being $100.

As such, the excess capacity of Canco2 is equal to $100 less (30% x $100) = $70 (as opposed to the full $100).

The anomaly arises because variable I of the “excess capacity” definition takes into account the absolute value of the taxpayer’s negative ATI.

And in situations where a taxpayer’s income inclusion under subsection 91(1) with respect to the IFR of an FA is reduced by a deduction under subsection 91(4) with respect to Canadian withholding tax applicable to such IFR, the taxpayer’s taxable income for the year would be less than the IFR. In the above example, Canco2 would have a FAPI inclusion under subsection 91(1) of $100 that is fully offset by a FAT deduction under subsection 91(4) of $100 (i.e., $25 FAT x RTF of 4), meaning Canco2 would have no taxable income for the year. Thus, when applying the ATI definition, Canco2 would have a nil balance under variable A (i.e., nil taxable income for the year) that would be reduced under variable C by the taxpayer’s IFR of $100, resulting in a negative ATI amount of $100 (before the negative amount is deemed nil by section 257).

The inappropriate outcome arises because the relief that is provided under variable G of the IFR definition for Canadian withholding tax is not properly reflected in the excess capacity definition.

A similar result can arise where a taxpayer and each Canadian group member elect to apply the group ratio under section 18.21, since subparagraph 18.21(2)(c)(iii) limits the total amount that may be allocated among Canadian group members to the total of all amounts, each of which would, in the absence of section 257, be the ATI of a member for each relevant taxation year. Thus, in a situation such as the one outlined above, because Canco2 would, in the absence of section 257, have a negative ATI amount, this would limit the total amount allocable under the group ratio.

Recommendation: Paragraph (a) of variable C of the ATI definition should be amended to ensure that a deduction under subsection 91(4) with respect to Canadian withholding tax that falls within variable G of the IFR definition is taken into account. In particular, paragraph (a) of variable C of the ATI definition could be reduced by “the portion of any amount in respect of income tax paid under subsection 212(1) that is deducted under subsection 91(4) in computing the taxpayer's income for any taxation year in respect of “foreign accrual tax” (as defined in subsection 95(1)) applicable to an amount that is included in the taxpayer's income under subsection 91(1) in respect of the relevant affiliate interest and financing revenues of a corporation that is a controlled foreign affiliate of the taxpayer at the end of an affiliate taxation year ending in the year.”

IFE and Real Estate Leases

The definition of IFE for a particular taxation year includes a “lease financing amount”, except in respect of a lease that qualifies as an “excluded lease”5 for the particular year. An “excluded lease” for a taxation year is defined to include a lease that is in respect of property that would be considered, at all times in the taxation year, exempt property for the purpose of subsection 1100(1.13) of the Income Tax Regulations6.

One category of exempt property under Regulation 1100(1.13) is a building or part thereof included in Class 1, 3, 6, 20, 31 or 32 in Schedule II other than a building or part thereof leased primarily to certain categories of entities. Regulation 1102(2) clarifies that a “building” does not include the land upon which the building was constructed or situated. Although an excluded lease should include a lease in respect of exempt property including the land on which the property is constructed or situated, this is not entirely clear under the current wording of the definition. A different interpretation would require lessees to calculate a lease financing amount in respect of the portion of their lease payments attributable to the underlying land, and such lease financing amount would not be excluded from the definition of IFE.

This issue affects virtually the entire retail sector — which typically leases space — and has implications for a wide range of other taxpayers across many industries. There does not appear to be a policy rationale for excluding from IFE the lease financing amount related to a building, but not the amount related to the underlying land. This interpretation would require many leases to be bifurcated into separate components — one for the building or common area, and another for the land — resulting in additional complexity, uncertainty and compliance burden.

Recommendation: The definition of “excluded lease” should be amended to clarify that it includes a lease in respect of property that is exempt property for the purposes of subsection 1100(1.13) of the Regulations, the land subjacent to the exempt property and any land immediately contiguous to such land that contributes to the use of the exempt property.

2. Share Buyback Tax

Subsection 183.3(2) generally requires a “covered entity” to pay a tax for a taxation year based on the fair market value of equity (other than substantive debt) that is redeemed, acquired or cancelled in the taxation year. The tax is reduced to the extent that the covered entity issues equity (other than substantive debt) in the same taxation year in a “qualifying issuance”.

Certain considerations in respect of the share buyback tax were addressed in our submission dated March 26, 2024. Members of the tax community have identified the following additional issues.

Substantive Debt

Paragraph (c) of the definition of “substantive debt” in subsection 183.3(1) requires, among other things, that the amount of any dividend (or other distribution) payable on the equity be calculated as a fixed amount, or by reference to a percentage of an amount equal to the fair market value of the consideration for which the equity was issued (which percentage is fixed or determined by reference to a market rate). Paragraph (d) of the definition requires, amongst other things, that the redemption amount of the share not exceed the total of the fair market value of the consideration for which the equity was issued, any unpaid distributions on the equity, and any early redemption premium, including for each such amount any amount that is attributable to foreign currency fluctuations.

It is typical for preferred shares to bear a dividend rate computed as a percentage of the redemption amount of the share, including where such redemption amount is more or less than the consideration for which the share was issued. For example, preferred shares may be issued at a discount to their redemption amount because market rates have increased by the time the equity is placed with investors. Preferred shares that pay a dividend based on a percentage of the redemption amount of the share may therefore not fall within paragraph (c) of the definition of “substantive debt” because the fixed dividend is not calculated by reference to the fair market value of the consideration for which the share was actually issued. Further, where the redemption amount exceeds the consideration for which the preferred share was issued, the requirements of paragraph (d) of the definition of “substantive debt” will not be satisfied.

In the foregoing circumstance, there does not appear to be a policy reason to exclude the preferred shares from the definition of “substantive debt”.

Recommendation: The definition of “substantive debt” in subsection 183.3(1) should be amended as follows:

- Paragraph (c) should be amended to explicitly include equity where the fixed dividend rate is computed by reference to the redemption amount of the share provided that such redemption amount is fixed at the time the equity is issued and the difference between the redemption amount and the fair market value of the consideration reflects an original issue discount or issuance premium not exceeding [15]%;

- Subparagraph (d)(i) should be amended to explicitly permit a redemption amount which is greater than or less than the fair market value of the consideration for which the equity was issued, provided that such redemption amount is fixed at the time the equity is issued and the difference between the redemption amount and the fair market value of the consideration reflects an original issue discount or issuance premium not exceeding [15]%.

Share Buybacks and Qualifying Issuances in Different Taxation Years

The share buyback tax is calculated on a taxation year basis. As noted above, the tax owing is reduced where a “qualifying issuance” occurs in the same taxation year as the redemption, acquisition or cancellation of shares. The share buyback tax can, however, apply in a punitive fashion where a qualifying issuance occurs within a short period of time before or after a redemption, acquisition or cancellation of shares, but in a different taxation year. The timing of public market share transactions are typically driven by non-tax commercial factors, such that a covered entity cannot necessarily accelerate or defer the timing of a public market share transaction in order to mitigate the tax consequences of transactions occurring in different taxation years.

Recommendation: Subsection 183.3(2) should be amended such that Part II.2 tax payable for a particular taxation year is reduced by the fair market value of equity issued in a qualifying issuance (i) made before the applicable balance-due date for that taxation year; and (ii) made within the [1] year period prior to the beginning of that taxation year (to the extent that such qualifying issuances have not reduced Part II.2 tax in any other taxation year).

3. Subparagraph 55(5)(e)(i)

Subparagraph 55(5)(e)(i) was amended by Bill C-208 and was not repealed or amended when the intergenerational transfer rules were passed.

This subparagraph expands the availability of the related party butterfly exception in paragraph 55(3)(a) to certain transactions between siblings by deeming siblings to be related where “the dividend was received or paid, as part of a transaction or event or a series of transactions or events, by a corporation of which a share of the capital stock is a qualified small business corporation share or a share of the capital stock of a family farm or fishing corporation within the meaning of subsection 110.6(1)” (underlining added). Such a share is referred to below as a “Qualifying Share”.

This purpose of this deeming rule in subparagraph 55(5)(e)(i) appears to be to allow distributions of property between siblings to qualify for the related party butterfly provision in paragraph 55(3)(a) (where none of the triggering events in paragraph 55(3)(a) occur as part of the relevant series of transactions). Without this exclusion, siblings would need to resort to the much more complicated and limited butterfly rule in paragraph 55(3)(b). Since this subparagraph was amended by a Private Members’ Bill, taxpayers do not have the benefit of extrinsic aids such as Explanatory Notes to help discern legislative intent. Members of the tax community have identified various technical uncertainties associated with this subparagraph.

Considerations Regarding the Relevant Time for Status of a Qualifying Share

In a related party butterfly transaction, there are at least two companies - a distributing company (DC) and a transferee company (TC) – and typically at least two deemed dividends: one deemed paid by the DC and received by the TC, and one deemed paid by the TC and received by the DC. The exception in subparagraph 55(5)(e)(i) treating siblings as related persons is only available where the dividend was received or paid by a corporation of which a share of the capital stock is a Qualifying Share, with a separate analysis being required for each dividend.

The time at which the characterization of a share as a Qualifying Share must be made is not explicit in subparagraph 55(5)(e)(i). In this regard, the provision refers to a dividend received or paid “as part of a transaction or event or a series of transactions or events”, but the same reference to series is not stated in respect of the time at which a share must be a Qualifying Share. The lack of clarity regarding the timing for a share to be a Qualifying Share creates a number of uncertainties. For example, purification transactions are typical and often necessary to meet the “small business corporation” definition required for QSBC share status, and accordingly it would often be the case that a share is not a Qualifying Share at all times during the relevant series of transactions. In addition, a share of the DC could initially qualify as a QSBC share but go offside briefly when the DC owns shares of the TC.

Share of a Corporation Not Owned by an Individual

By definition, a Qualifying Share is a share of an individual. Thus, if at the relevant determination time the share is not owned by an individual, the exception in subparagraph 55(5)(e)(i) for Qualifying Shares may not be met. For example, two sibling farmers may have previously carried out a “Holdco Freeze” and have since redeemed all their personally held freeze shares in the active farming corporation (“FarmCo”) leaving the holding corporations owning all of the shares of FarmCo. Even if all or substantially all of the shares of FarmCo are attributable to active farming activities, the sibling exception in subparagraph 55(5)(e)(i) may be unavailable because no shares of FarmCo are owned by an individual. An unusual feature of the exception is that it would seem to be available if even one share was owned by a sibling; in that case “a” share would be a share of the capital stock of a family farm or fishing corporation. From a policy perspective, such an immaterial difference should not determine whether subparagraph 55(5)(e)(i) applies.

The requirement that a Qualifying Share be owned by an individual also appears to preclude sequential paragraph 55(3)(b) spin off transactions in the context of shareholders who are siblings.

Recommendation: Subparagraph 55(5)(e)(i) should be amended to more clearly describe the circumstances in which siblings are related for the purpose of section 55, including clarifying the time at which a share must be a Qualifying Share and allowing otherwise Qualifying Shares to be owned by a corporation in appropriate circumstances.

4. Foreign Accrual Business Income

Budget 2022 proposed changes to the taxation of income earned by controlled foreign affiliates (CFAs) of Canadian-controlled private corporations (CCPCs) and substantive CCPCs. These changes aim to eliminate the tax deferral advantage available when such corporations earn investment income through CFAs. If this income had been earned directly by the CCPC or substantive CCPC, it would have been subject to the higher tax rate applicable to “aggregate investment income”.

The net tax payable in respect of “foreign accrual property income” (FAPI) is determined using the “relevant tax factor” (RTF). Pursuant to subsection 91(4), a taxpayer which has an income inclusion in respect of FAPI can generally deduct an amount equal to the RTF multiplied by the “foreign accrual tax.” Without the recent amendment, the RTF would be 4, fully offsetting the FAPI inclusion when the foreign tax rate is 25%—significantly lower than the ~50% tax rate applicable to aggregate investment income earned directly by a CCPC or substantive CCPC.

The Department of Finance published draft legislation on August 12, 2024 that would effectively subject FAPI earned by CFAs of a CCPC or substantive CCPC to different Canadian corporate income tax rates depending on the nature of the FAPI. The draft legislation proposes that the RTF for FAPI earned by a CCPC or substantive CCPC will be 1.9 unless the FAPI relates to “foreign accrual business income” (FABI) or “FABI surplus” in which case the RTF can be 4 if an election is filed. The RTF of 1.9 would require that the rate of foreign tax be 52.63% to completely offset the FAPI income inclusion.

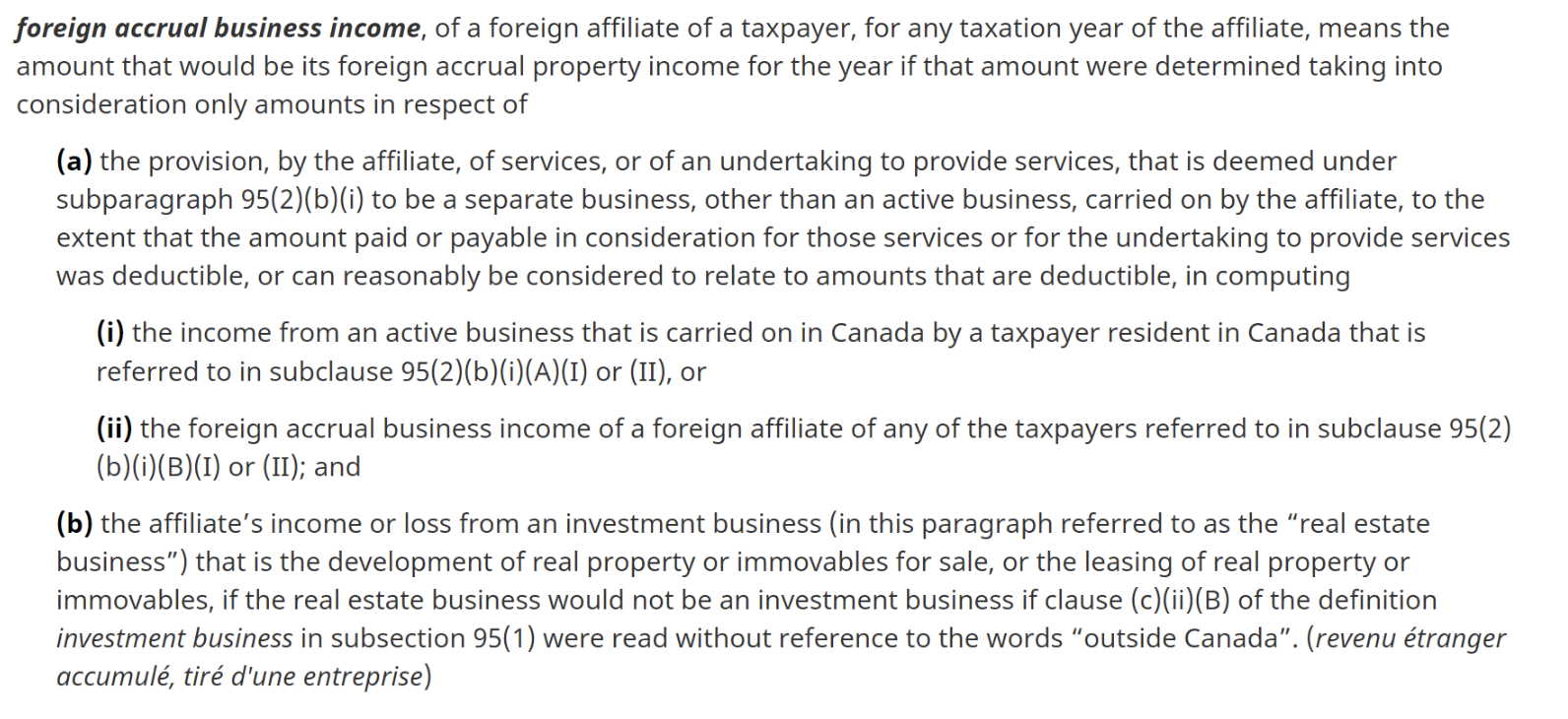

Proposed subsection 93.4(1) defines FABI as follows:

Several commentators7 have noted that the proposed definition of FABI is too narrow and will not include certain income earned by CFAs that would not be considered to be aggregate investment income had it been earned directly by the CCPC or substantive CCPC. Examples of such income include income from developing real estate for sale, or from leasing personal property, where the CFA employs fewer than five full time employees. The definition of FABI should be revised to include all income that would not be aggregate investment income had it been earned directly by a CCPC or substantive CCPC.

Recommendation: The definition of FABI should be amended to include all income which would not be aggregate investment income had it been earned directly by the CCPC or substantive CCPC.

5. Subsection 220(3.2) and Regulation 600

Subsection 220(3.2) provides the Minister of National Revenue with the discretion to extend the time for making an election, or to grant permission to amend and revoke an election, but only where that election is otherwise required to be made under a prescribed provision. Regulation 600 sets out these provisions. We submit that subsection 220(3.2) should be amended to give the Minister the discretion to permit the late filing, amendment or revocation of any election under the Act in appropriate circumstances, without reference to Regulation 600. In particular, the Minister should not be precluded from granting relief where she determines that such relief would be fair and reasonable, simply because the election is not specifically set out in Regulation 600. This would also be consistent with the recent decision of the Federal Court of Appeal in Onex Corporation v. Canada8 suggesting that taxpayer relief provisions should be given wide construction to enable them to serve their remedial purpose.

Recommendation: Subsection 220(3.2) should be amended to eliminate the reference to a prescribed provision, and Regulation 600 should be repealed.

6. Part VI.1 Tax and Non-Resident Shareholders

Pursuant to section 191.1, every taxable Canadian corporation which pays a taxable dividend (in excess of the dividend allowance) on taxable preferred shares is liable to pay a tax equal to 25% or 40% of the amount of the dividend paid. There is an exception for dividends paid to shareholders having a substantial interest in the corporation, which includes shareholders who are related to the corporation, but excludes a partnership unless all of its members are related.

Part VI.1 tax was introduced in 1988 in order to make the tax system more neutral as between debt and preferred share financing. As stated in the Technical Notes “These rules are designed to eliminate the benefits from the use of preferred shares as a form of after tax financing. By issuing preferred share in lieu of debt, non-taxpaying corporations are able to transfer the tax benefit of accumulated losses, deductions and tax credits to the holders of the preferred shares, generally taxable corporations, resulting in significant loss of tax revenues to the government.” Changes in the Act and applicable treaties (including the elimination of withholding tax on arm’s length interest) since 1988 suggest that the concerns which underlie Part VI.1 tax may no longer be applicable, particularly in respect of non-resident shareholders.

Where the shareholder of the taxable preferred shares is a non-resident person, the policy behind Part VI.1 tax is inapplicable. Since 2008, a non-resident investor who deals at arm’s length with the Canadian corporation is not subject to Canadian tax on interest paid by the Canadian corporation, so there is no incentive to switch to preferred shares in order to minimize Canadian tax. A non-resident investor who does not deal at arm’s length with the Canadian corporation (and who is not entitled to the benefits of the Canada United Stated Income Tax Convention (the “Treaty”)), may be subject to Canadian withholding tax on the payment of interest, but that investor would likely have a substantial interest in the Canadian corporation and the corporation would not pay Part VI.1 tax in any event.

A non-resident investor subscribing for preferred shares of a Canadian corporation does not acquire the benefit of the Canadian tax losses, deductions and tax credits through the acquisition of these shares. In fact, a non-resident investor is likely to pay more Canadian tax on a preferred share investment than a debt investment, as interest paid to arm’s length lenders or lenders entitled to the benefits of the Treaty is not subject to Canadian withholding tax. Conversely, dividends paid to non-resident shareholders are always subject to Canadian withholding tax. However Part VI.1 tax often acts as a deterrent to a non-resident investment in preferred shares of an unrelated Canadian corporation where the Canadian corporation cannot use the full deduction under paragraph 110(1)(k) on a timely basis. As a result, non-resident investors are often compelled to instead invest through a debt instrument (resulting in a deduction to the Canadian borrower and no withholding tax on the interest payments). This issue often arises in connection with proposed investments by non-resident private equity funds in Canadian businesses.

Recommendations: The definition of “excluded dividend” in subsection 191(1) should be amended to include dividends paid by a corporation to a non-resident person. Subsection 191(6) should also be amended such that it refers to this new type of excluded dividend. It should also be considered whether Part VI.1 in its entirety no longer serves a function and should be repealed.

7. Flipped Property Rules

The flipped property rules were included in Budget 20229 to reduce the pressure on housing prices in Canada. The Budget described “property flipping” as “buying a house and selling it for much more than what was paid for it just a short time prior”10 (emphasis added).

Subsection 12(12) deems a gain from the disposition of a “flipped property” to be income from an adventure or concern in the nature of trade with respect to the flipped property and not to be a capital gain. The definition of “flipped property” in subsection 12(13) refers to a sale of a housing unit or a right to acquire a housing unit (“real property”) in Canada owned (or held) by the taxpayer for less than 365 consecutive days prior to its disposition, unless the disposition can reasonably be considered to occur due to, or in anticipation of, one or more of a list of events. Those events are listed in paragraph 12(13)(b).

We submit that the exceptions in paragraph 12(13)(b) are overly narrow such that the flipped property rules may apply in inappropriate situations given the underlying tax policy rationale for these rules. First, the rules generally do not provide ownership period continuity when one taxpayer acquires real property from a non-arm’s length person. Second, the rules fail to accommodate situations where an estate, administered by an arm’s length trustee, sells real property formerly owned by a deceased individual within 365 days of their death. Each of these concerns is described in more detail below.

Transfers between Non-Arm’s Length Persons

The following are examples of situations where the “flipped property” rules could apply in an inappropriate manner when a taxpayer acquires real property from a non-arm’s length person.11 All examples assume that the real property is capital property which, absent the application of the flipped property rules, would result in a capital gain.

Transfer of Real Property to a Spouse

A transfer of capital property between spouses generally occurs on a rollover basis12. The attribution rules deem any capital gain resulting from a subsequent sale by the transferee spouse to be a capital gain of the transferor spouse13. The capital gain attributed to the transferor spouse should not be from a “flipped property” if the transferor spouse owned the property for 365 days or more prior to the disposition. However, if the transferor spouse owned the property for fewer than 365 days, and the combined ownership period of both the transferor and transferee equals 365 days or more, the property flipping rules should not apply. However, the transferee spouse’s ownership period is not attributed back to the transferor spouse.

Alternatively, the transferor spouse might “elect out” of the automatic spousal rollover so that the attribution rule in section 74.2 does not apply. In this case, the “flipped property” rules would likely apply to a sale by the transferee spouse where the transferor spouse owned the property for 365 days or more and the transferee spouse sold the property within 365 days of the transfer.

In both cases, there does not appear to be a policy reason for the gain to be taxed on income account. The flipped property rules should consider the combined ownership period of both spouses to align with the broader policy intent. The purpose of the flipped property rules is to deter speculative short-term sales, but when the property has been held collectively by spouses for a year or more, there would not appear to be the type of rapid turnover that the rules are designed to target.

Transfer of Real Property to a Corporation on a Rollover Basis

The “flipped property” rules do not include a continuity of ownership rule where real property is transferred to a corporation from a non-arm’s length person on a tax-deferred basis. If the corporation then sells the property within 365 days of the transfer, the sale would be considered a disposition of a “flipped property,” and the resulting gain would be taxed as business income. This outcome arises despite whether the property was owned within the same related group for more than 365 days, which seems inconsistent with the broader policy intent of the rules.

Recommendation: The “flipped property” rules should be amended to aggregate the period of ownership of non-arm’s length persons.

Amalgamations and Wind-Ups

An amalgamation could cause real property that would otherwise not be “flipped property” to become “flipped property” if sold within 365 days of the amalgamation. For example, a corporation (RealCo) could have owned real property for many years. RealCo might amalgamate with another corporation on a tax-deferred basis under section 87 to form “Amalco”.

Amalco is deemed by paragraph 87(2)(a) to be a new corporation. A sale by Amalco within 365 days of the amalgamation would be a disposition of a “flipped property”, with the resulting gain taxed as business income. The same issue arises on a winding up of RealCo into its parent corporation under section 88.

The treatment of the gain as business income in this scenario does not align with the policy intent of the rules as the property was held for a long-term rental purpose before the amalgamation or wind-up.

Recommendation: For the purpose of determining whether a property is a “flipped property”, (i) an amalgamated corporation should be considered the same corporation as, and a continuation, of its predecessors; and (ii) the ownership period of a predecessor corporation in a winding-up to which subsection 88(1) applies should be included in determining whether the 365-day test is met by its parent corporation on a later disposition of the property.

Trust Rollout using 107(2)

A trust may distribute real property to a capital beneficiary on a tax-deferred rollover basis under subsection 107(2). However, no rule deems the capital beneficiary to have owned the property for any period before the distribution. As a result, a trust could distribute real property which it held for at least 365 consecutive days, yet if the capital beneficiary sells the property within 365 days of the distribution, it would be considered to be “flipped property,” and any gain on disposition would be taxed as business income.

Recommendation: For the purpose of determining whether a property is a “flipped property”, the period of ownership by a trust should be included in determining whether the 365-day test is met for a beneficiary who acquires the property by way of a tax-deferred distribution under subsection 107(2).

Property acquired by an Estate

One exception in the “flipped property” definition relates to the disposition of real property by a taxpayer due to or in anticipation of the death of the taxpayer or a person related to the taxpayer.

A deceased taxpayer is not always related to their estate, which could result in the “flipped property” rules applying when an unrelated estate sells real property acquired from the deceased within 365 days of death. There seems to be no policy rationale for taxing gains realized by an estate as business income under the “flipped property” rules in such cases, especially where the rules would not have applied to the deceased taxpayer on a sale prior to death.

Recommendation: Add to the list of exclusions in subsection 12(13) the disposition of property by a graduated rate estate, where the property would not have been “flipped property” if sold by the deceased individual immediately prior to death.

8. Common Reporting Standard

The Common Reporting Standard (CRS) requires financial institutions to identify accounts held by non-resident persons and report certain information relating to those accounts to the CRA.

Guidance published by the CRA indicates that financial institutions are subject to penalties for late filing and failure to file electronically CRS reports under subsections 162(7.01) and (7.02) respectively14. However, we note that neither Regulation 205(3) nor Regulation 205.1(1) lists CRS information returns.

Recommendation: Regulations 205(3) and 205.1(1) should be amended to include CRS information returns.

End Notes

1 In CRA Document 2016 – 0661071R3, the CRA confirmed that, where section 80 applies, it would apply in priority to section 143.4.

2 Canada, Department of Finance, A Recovery Plan for Jobs, Growth, and Resilience: Budget 2021 (Ottawa: Department of Finance, 2021) at 306.

3 Subparagraph 251.1(4)(d)(iv) also expands the affiliated test for trusts based on blood relationship, marriage and adoption.

4 Pursuant to subsection 132(7), a mutual fund trust cannot be established or maintained primarily for the benefit of non-resident persons.

5 ITA 18.2(1) “interest and financing expense” (g).

6 ITA 18.2(1) “excluded lease” (c)(ii).

7 See for example Christopher Montes, John Farquhar and Evan Raymer, “Mind the Gap: FABI Relief Falls Short for CCPCs” (2024) 3:4 International Tax Highlights 2 and Hetal Kotecha and Daryl Maduke, “Impact of Capital Gains Realized by Foreign Affiliates and Treatment of Other Income” (2024) 3:4 International Tax Highlights 3.

8 2024 FC 1247.

9 Canada, Department of Finance, Budget 2022: A Plan to Grow Our Economy and Make Life More Affordable (Ottawa: Department of Finance, 2022).

10 Ibid at 49.

11 See Evan Crocker and Kenneth Keung, “Related-Party Transfers and the Flipped-Property Rules” (2023) 23:2 Tax for the Owner-Manager.

12 ITA subsection 73(1).

13 ITA subsection 74.2(1).

14 See Canada Revenue Agency Guidance on the Common Reporting Standard at paragraph 12.1.