(uniquement en anglais)

par Daekwon Blair1, 2025 winner of the Labour and Employment Law Section Student Essay Contest.

The private-sector organized labour force in Ontario is confronting an accelerating substitution threat as automation, digital technology, and artificial intelligence (AI) deskill & displace jobs at an aggressive rate. In Industry 4.0, Ontario can best protect the values of fairness and industrial peace within the industrial relations ecosystem by legislating technology change provisions in the Labour Relations Act, 1995 S.O. 1995, c. 1, Sched. A. These provisions should be embedded in a triadic governance framework that is grounded in Kochan et. al’s (1983) Strategic Choice Model. In this view, collective bargaining can remain a tripartite process. A process where employers define skill needs in the digital age, the government pairs legal mandates with incentives, and unions safeguard job security through lifelong learning and coordination.

“The law on its own is just a series of words and rules. Unless it’s something that contributes to the possibility of justice, it’s essentially unfulfilled.”2 – Justice Rosalie Abella

I. Introduction

The labour markets of today that operate within liberal democratic states have largely undergone restructuring due to shifts in arrangements of global markets (globalization),3 improvements in information communication technologies (ICT), and advancements in digital technological innovation.4 In the present day, these pressures have collectively generated what some scholars, such as Lang Li (2024), refer to as Industry 4.0. Industry 4.0 or the fourth wave of industrialization marks a dramatic shift in the configuration of labour markets globally.5 Markets, and by extension, firms are globally connected with capital, supply, and in some cases even labour flowing freely across borders.6 Much of this restructuring has been facilitated, at least in part, by the growing integration of digital technologies into several aspects of the firm (work) and society as a whole.

To respond to the substitution threats facing private-sector unionized industries in Ontario, the industrial relations systems in Canada must undergo a series of legal, regulatory, and strategic reforms. These reforms should be grounded in a triadic governance approach that understands the strategic choices of actors in the industrial relations system and implements mandatory bargaining on technology change to insulate organized private-sector workers from the pending substitution threat. Kochan et. al’s (1983) Strategic Choice Model,7 and Hopster and Maas’s (2024) Technology Triad,8 provide a rich foundation for proposing tailored reforms to labour relations in Ontario. Whereas the strategic choice model understands the relationships between actors in the industrial relations ecosystem through dyads, “… the triadic model enables more effective and meaningful triage among many technological changes, [at work], helping to identify where these may, [pose the greatest substitution threat], and where, [legislative], and regulatory interventions are most urgently needed.”9

II. Background

Previous waves of industrialization have shown firms the transformative and competitive power of digital technology. The incorporation of a business strategy or strategic decision that favours automation is viewed not only as efficient, but essential, “… for a competitive advantage [in the market].”10 Given the conditions that underscore Industry 4.0, turning toward automation would be a sound strategic decision for firms seeking to remain competitive, increase productivity, and ultimately meet the bottom-line goal of growing total revenue.11 The rise of machine learning (ML), robotic technology, the Internet of Things (IoT), algorithmic management,12 artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and digitized workflows signal an intensification of technological substitution or substitution threats.13

The term “substitution threat” as used in this analysis refers to the potential for digital technology and tools to displace (and in some cases replace) and deskill human workers from their tasks at work, or entire jobs. A substitution threat occurs when firms make business decisions that result in investments in technological change and automation. This often includes the integration of autonomous technology or machine labour at work. Substitution threats generated by technological change and automation in the workplace are not new occurrences in the ecosystem of work. Human labour has historically experienced justified anxieties in response to automation that renders the need for their labour, human labour in the firm, redundant. The Luddite movement of the 19th century presents one of the earliest recorded cases of human fears and anxieties manifesting in response to the substitution threats brought about by the introduction of automation.14 The first wave of the Industrial Revolution (Industry 1.0), which lasted from about the late 1700s to the early 1900s, introduced machinery into the world of work in ways that, “workers opposed”.15

The substitution threats facing human labour in the pending technological changes occurring at work during Industry 4.0 will be unlike former periods of automation. The speed, force, and reach of technological disruption will be unlike any technology shock experienced in the world of work – unprecedented.16 Historically, substitution threats in the past, such as the one that served as a catalyst for the 19th-century Luddite movement, were largely biased to skills (skills-biased). Meaning that previous waves of automation threatened middle-skilled and low-skilled workers, leaving high-skilled workers largely insulated from substitution threats.17 This is largely because, “technology substitutes for skills through the simplification of tasks,”18 leading to deskilling and job loss (substitution), in jobs previously believed to be secure. The ability of high-skilled workers to withstand substitution threats often signalled that education, at least in part, played a role in supporting human labour, serving as a buffer or insulation between substitution shocks. Previous waves of automation have created downward pressures on the, “…demand for skilled and knowledge workers, and fewer opportunities for unskilled workers, [‘in labour markets such as Canada’s which are classified by high wage rates’],… .”19 The narrative is very different in Industry 4.0, given the rise of digital integration and the new capabilities of autonomous technologies. Although, as De Stefano and Taes (2022) note, “… automation of business organisations can occur without a hint of AI being involved”,20 firms are increasingly turning to automated systems that incorporate artificial intelligence and algorithms. In Industry 4.0, low-skilled, middle-skilled, and high-skilled workers alike are susceptible to displacement. The technology powering autonomous machine labour in firms is capable of completing tasks in the workplace that span across all skill levels (low, middle, and high-skilled levels).21 The substitution threat and its promise to deskill and replace human labour have matured into a shared or common risk facing workers possessing various degrees of skill.

III. The Claim*

The changes to the world of work raise a necessary and critical question about the future of work in Canada: how should (and might) Canada’s industrial relations ecosystem respond to the substitution threats in a manner that supports distributive fairness, protects private sector organized workers, and facilitates lasting industrial harmony and peace in Industry 4.0? The strategic pursuit of competitive advantages through digital transformation and restructuring in Canada has created a gap for private sector organized labour. Adversarial attitudes and decentralized labour policy at the provincial levels have failed to provide unionized private sector workers with a coordinated legal and strategic response to the threats posed by automation-driven substitution and de-skilling. Canadian labour law, in its current manifestation, has not evolved at a pace fast enough to adequately respond to the substitution threats facing human labour. To protect private sector organized labour in Ontario, the industrial relations ecosystem must undergo a series of legal, regulatory, and strategic policy reforms. These reforms should be guided by Kochan et al. (1983) influential Strategic Choice Model for Industrial Relations,22 and a transplant of Hopster and Maas’ (2023) Technology Triad,23 into the Ontario framework to usher in a new regime of labour law and regulation that protects workers from substitution threats in Industry 4.0 while promoting industrial peace.24 25 A triadic governance framework for Industry 4.0 would require strategic coordination from network stakeholders: governments, employers, and bargaining agents (trade unions), to shift Ontario’s industrial relations ecosystem to adopt mandatory bargaining on technological change (unless otherwise agreed to in a collective bargaining agreement), and coordinated tripartite efforts to support workers impacted by substation shocks through upskilling and reskilling programs.26

Similar to a “legal transplant”, this study aims to defend the claim that Ontario (and Canada generally) is a suitable “subject” for a transplant of the Technology Triad. The governance framework can be used to coordinate a path forward in Industry 4.0 that is beneficial to all stakeholders in the industrial relations ecosystem: Employers (firms/management), Bargaining Agents (Trade Unions and Associations), Governments (provincial and federal), and Employees. Due to the tripartite nature of labour relations in Canada, (individual) Employees are typically not accounted for in the mix of network stakeholders relevant to the ecosystem. However, the substitution threat will require employees to take an active role to ensure gains achieved at the table through collective bargaining do not succumb to substitution shocks. Employees will also need to take an active role in signalling job readiness in the face of the strategic business decisions to integrate machine labour and restructure the firm to remain competitive and improve productivity.27

Salaymeh and Michaels’ (2022) study was especially helpful in understanding the difficulty of legal transplants as a concept (and in comparative law).28 Legal transplants are often used as a tool in comparative legal studies. The goal in this analysis is to borrow the concept/tool to facilitate a mapping of a technology triad to industrial relations policy. One claim that the ‘decolonist approach’ in the context of comparative law cites as a drawback to legal transplants may be a benefit in the context of industrial relations, underscored by a triadic strategic choice model. The ‘inherent hierarchy that is associated with the transplant recipient and donor relationship’ is arguably already accounted for in Canada’s legal framework and industrial relations ecosystem through the constitutional division of powers. In Canada, the constitutional division of powers ensures, “…as a general principle, labour relations and working conditions fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the provinces… .”29 In Ontario Hydro v. Ontario (Labour Relations Board) (Ontario Hydro), 1993 CanLII 72 (SCC) (at p.427),30 the Supreme Court of Canada held that, “… control over labour relations…,” does not impede Federal jurisdiction. The hierarchical concern associated with legal transplants does not inherently hinder the effectiveness of adopting provisions from the Canada Labour Code,31 into Ontario’s Labour Relations Act, 1995 S.O. 1995, c. 1, Sched. A.32 The industrial relations system in Canada is structurally suitable and primed for a transplant, due to its decentralized nature.

IV. Redefining the Substitution Threat in Industry 4.0

Similar to many aspects of Industry 4.0, substitution threats are emerging across industries at an aggressive pace and force. Li (2023) notes that, “skills gaps are inevitably increasing [in Industry 4.0], unless today’s workers… learn new technology and take the opportunity to acquire the skills [necessary to signal job readiness], and required for future employment.”33 Unlike traditional skill-biased technological change that views low-skilled workers as being most at risk, Industry 4.0 exposes high-skilled and middle-skilled workers to the dangers of substitution threats.34

The COVID-19 pandemic serves as a clear example of the disruptive force and nature of technology in society (particularly liberal democratic states) and the workplace. In response to public health and safety regulations and business operation needs, digitization was rapidly intensified during the pandemic. Arrangements such as remote work, video conferencing for various organizational meetings, and the widespread use of electronic monitoring became normalized during the COVID-19 pandemic in North America. These accelerated technological shifts made during the pandemic have contributed to the emergence of a skills gap. In particular, new skills such as digital competencies, which were not viewed as essential skills in traditional frontloading education models, are now essential. A 2023 Future of Jobs Report from the World Economic Forum (WEF) finds that education does not serve as a sufficient barrier to digital upskilling and reskilling.35 The World Economic Forum’s findings suggest that lifelong learning is accessible for all workers facing a substitution threat, regardless of one’s original level of formal education.36 A Bank of Canada/Banque du Canada “Staff Discussion Paper” (2023) on the digitization of labour markets further confirms this observation, noting that the results suggest more than fifty-percent (50%) of 2019 job postings in countries such as, “… Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Singapore and the United States…,”37 post-pandemic required some form of ‘digital skills to be a qualified and competitive applicant’.38 The same “staff discussion paper” (2023) underscores another factor of Canada’s labour market related to the substitution threat and automation. Canada’s dependence on an old-age or aging workforce has continuously been trending upwards, creating a, “…scarcity of middle-aged workers,”39 which risks influencing firms toward machine labour and automation in industries currently reliant on the shrinking supply of middle-skilled human labour. The potential negative outcomes the substitution threat presents to human labour (especially private sector organized labour) are directly tied to the broad values and principles that underscore Canadian labour relations and labour law. Values such as fairness, distributive justice, collective bargaining, and industrial harmony. If the strategic decisions about automation and the future of work are made independently at the firm level, absent adequate labour protections and incentives promoting industrial harmony and collective bargaining, the effectiveness of Canada’s industrial relations ecosystem will be eroded. In Industry 4.0, a sound industrial relations ecosystem underpinned by fair collective bargaining in pursuit of, “… a just share of the fruits of progress to all…,”40 must provide more than wage benefits and stability – it should also provide opportunities for growth (upskilling and reskilling) and resilience to the substitution threat.

V. The Strategic Choice Model for Industrial Relations

A model able to withstand the disruptiveness of digital technology is needed to guide the strategic choices network stakeholders make during Industry 4.0. Kochan, T., McKersie, R., and Cappellei’s, P (1983) Strategic Choice and Industrial Relations Theory, understands industrial relations as an interconnected network of stakeholders who make strategic decisions, “… determined by a continuously evolving interaction of either the environment pressures and organizational responses.”41 Kochan et al.’s (1983) theory provides a suitable paradigm to understand how network stakeholders (the government, firms, trade unions, and employees*), navigate the changing nature of the future world of work. Network stakeholders navigating the substitution threat and changing workplaces more generally, make strategic decisions when the following conditions are present: (1) the parties possess the freedom to choose from a bundle of choices (multiple courses), “… where environmental constraints do not overpower the ability of the parties to choose alternative courses of action.”42 (2) any decision made is dynamic and must, at least aim to adapt to the shifting pressures of the market, “… that alter a [network stakeholder’s], role or its relationship with other [network stakeholders] in the industrial relations system.”43 As presented, Kochan et. al’s (1983) strategic choice model is driven by organizational responses from network stakeholders and environmental pressures. Restructuring the firm and its operations with technological investment to remain, “… competitive with respect to prices,”44 is an example of strategic decision making from organizations (management). In Industry 4.0 the attractiveness of machine labour and automation ‘leads firms to adjust, “… their emphasis in industrial relations away from maintaining labo[u]r peace in order to maximize production… [and increase] productivity in order to [maintain steady], growing price competition.”45

The strategic choice model as presented by Kochan et. al (1983) is valuable for understanding decision-making that occurs within the industrial relations system, but suffers from a structural issue. The strategic choice model understands collective bargaining in industrial relations through a dyadic lens.46 A dyadic lens characterizes collective bargaining as a bilateral exchange between trade unions (bargaining agents) and employers (management) within the regulated boundaries of labour relations. During this bilateral exchange, management and bargaining agents engage in a “give and take”relationship, negotiations, where concessions and tradeoffs are made to achieve each party’s interests.

While this two-sided dyadic approach captures the traditional dynamic relationship between parties engaged in collective bargaining at the negotiating table, it struggles to capture the complexity of the industrial relations ecosystem in Industry 4.0. Strategic decision making at the firm level related to technological change, such as algorithmic management,47 artificial intelligence, and automation, is increasingly influenced by pressures sourced outside the bargaining table. These pressures include, but are not limited to: changes in government policy and in the, “… political environment…,”48 the fissuring of work,49 the rise of platform work, and shifting labour market demands driven by, “… technological change that has decreased the relative demand for less credentialed labo[u]r.”50 In the fourth wave of industrialization, the role of workers in the industrial relations system should be reconceptualized. Workers will need to become more active in their efforts to engage in lifelong learning to obtain the knowledge, skills, and competencies necessary to withstand substitution shocks. As firms continue to engage in strategic decision making that favours technological change for the future of work, the, “…demand in Canada for [digitally and industry informed] skilled workers relative to unskilled workers…,”51 will likely increase. The traditional (dyadic) framework used to understand collective bargaining and labour relations must be expanded and mapped on a technology triad to capture the new dynamics of industrial relations in Industry 4.0.

5.1 CLEARING THE HURDLE: MEETING THE ‘DEFINED CONDITIONS’52

The two conditions Kochan et. al propose in their 1983 study are met in the Ontario context, making it a suitable case for an application of the ‘strategic choice model for industrial relations’. The industrial relations system in Ontario, as it relates to private-sector organized labour, gives employers discretion over technological change and automation strategies, meeting Kochan et. al’s (1983) first condition. Decisions related to management rights, technological change, and automation go well beyond, “…minor or trivial decisions over which parties [normally] have discretion [over].”53

5.2 Modernizing Kochan et. al’s Strategic Choice Model

Although dated, Kochan et. al’s (1983) model is still very beneficial for accurately understanding the strategic choices actors make within the industrial relations system. Historically, the strategic choice model has been adequate to address matters related to substitution threats in previous waves of industrialization. Yet, like many traditional frameworks in Industry 4.0, Kochan et. al’s model struggles to adequately address complex changes generated by the integration of digital technology during the current wave of industrialization.54 The current wave of industrialization cannot be understood, theoretically conceptualized, or regulated effectively through a traditional framework using a dyadic lens. Hopster and Maas (2024) technology triad presents a suitable path for the strategic choice model in industrialization to be used as a base to ‘more accurately understand and triage how workers will engage with and experience substitution threats from technological changes’ at the firm.55

VI. The Technology Triad: A Framework for Coordinated Strategic Responses

To supplement the limitations of Kochan et. al’s (1983) strategic choice model, Hopster and Maas’ (2024) framework can be applied. Hopster and Maas (2024) propose a framework known as the “Technology Triad”, which is beneficial for understanding technological change at work in Ontario and what the most suitable legal, regulatory, and ethical responses might include. Similar to the makeup of industrial relations in Canada, the technology triad underscores tripartite responses that integrate perspectives from law, ethics, and technology. Triadic mapping, a core component of the triadic approach, differs from traditional frameworks rooted in dyads. Rather than treating each actor in a dyadic silo, triadic mapping enables all members of the industrial relations system to collectively, “...identify new priorities, strategies, or considerations for, [the correct] societal (ethical and/or legal) responses to an emerging technology.”56 A coordinated understanding of all the relevant information needed to make strategic decisions, between actors in the industrial relations system, allows all actors to make more informed decisions about strategy (organizational, negotiations, and political), and industrial priorities in the current disruptive wave of industrialization. If applied with the correct provincial legislative and regulatory support to labour relations and the future of work, network stakeholders can enhance the strategic choice model into a triadic industrial relations strategy for Industry 4.0. A triadic industrial relations strategy would require employers, unions, and the Ontario government to create the conditions necessary to promote collective bargaining that balances fostering innovation in the firm through automation and insulating as many workers as possible from substitution shocks in a fair manner.

6.1 Operationalizing the Technology Triad

There are several steps that Hopster and Maas (2024) lay out to operationalize a triadic approach (triadic mapping). The first step is to identify a relevant technological challenge, such as the substitution threat, that has the potential to pervert traditional moral, legal, and policy frameworks. The substitution threat to private-sector organized labour in Ontario also meets the criteria of being an ‘ongoing, technologically complex, and normatively significant challenge’.57 The second step to triadic mapping is to conduct an evaluation of the current dyadic approaches within the industrial relations system that have been taken to address previous waves of substitution threats. In the Canadian context, interrogations of technological change in Industry 4.0 from the perspectives of ‘law-ethics, law-tech, and tech-ethics’,58 are dominated by dyads. For example, discussions about algorithmic management at work are often focused on surveillance and privacy.59 Similarly, discussions about digital technology, algorithms, and discrimination focus on ethics and substantive equality.60 What is missing from both these rich narratives is a holistic understanding for making workers more resilient from all perspectives.61 The third step to operationalizing triadic mapping is an integration of existing siloed accounts into a technology triad.62 Triadic mapping enables access to a more informed identification and understanding of the ‘legal, ethical, and regulatory disruptions’ that flow from technological change in organized industries.63 Kochan et. al’s (1983) model does not need to be replaced because of currency limitations. Supplemented with triadic mapping, a suitable path forward can be identified.

VII. ‘Is Labour Law Still Enough?’: A Mini-legislative Analysis and Reform Proposals

Canadian labour law and its decentralized posture is not prepared to address the substitution threats during the fourth wave of industrialization. While there is an argument to be made that the Canada Labour Code contains provisions regarding technological change under sections 51-55,64 no congruent provisions exist in Ontario’s Labour Relations Act.65 Due to the decentralized nature of industrial relations in Canada, s.51-55 of the Canada Labour Code does not extend coverage to private-sector organized industries in Ontario.66 67 The provisions related to technology change in the Canada Labour Code promote harmonious industrial relations during periods of technology shocks, by requiring employers to provide bargaining agents with 120 days of notice for strategic decisions related to technological change,68 provide details (in writing) to inform union decision making about the changes,69 and promoting collective bargaining on the issue of technological change.70 The clauses embedded within sections 51-55 of the Canada Labour Code,71 attempt to ensure principles of procedural and distributive fairness are not eroded in the industrial relations system due to industrialization.

An internal transplant of sections 51-55 into Ontario’s labour legislation would establish an additional minimum floor protection for workers facing the substitution threat and firm restructuring. A transplant would also ensure that strategic decisions around technological change are negotiated at the bargaining table, where concessions can be made, and not simply imposed on private-sector organized industries. In line with s. 54 of the Canada Labour Code,72 a transplant into the Ontario legislation, would enable bargaining agents, “…to assist the employees affected by, [substitution threats] to adjust to the effects of the change… [through], collective bargaining for the purpose of, [revis[ing] existing provisions in the collective agreement or including additional provisions].”73 Legislative reform would promote harmonious industrial relations by ensuring, “…an ongoing relationship between labour and management…,”74 underscored by collective bargaining in good faith,75 on automation and technological change. I wish to stress a point illustrated by The Honourable Warren K. Winkler, (former) Chief Justice of Ontario (2011), to maintain a productive and harmonious industrial relations ecosystem, ‘collective bargaining should continue to be the primary mechanism used to define the terms of employment and govern the relationship between parties in organized enterprises’.76 Collective Bargaining allows parties to, “…cope with [technological] challenges fairly flexibly by taking into account [the] interests of workers [(represented by bargaining agents)], and employers.”77

VIII. Triadic Stakeholder Responsibilities to Address the Substitution Threat

8.1 Employers at the Firm Level (Management)

Each network stakeholder has a shared role to play in a triadic response to automation and substitution shocks. Employers have access to the greatest amount and most accurate labour market information necessary to identify emerging labour demands (and their accompanying skill competencies).78 Employers should take up a position as a leader in defining the digital and industry-specific skills that will be required for the future of work in Industry 4.0. Firms should also strategically choose to integrate on-the-job reskilling into their business strategy. The gains that can be achieved from having a resilient, skilled workforce of human labour should not be overlooked – a focus on training is a win-win scenario.79

8.2 Governments

The Ontario Government has a considerable (and central) role to play, with both a carrot and a stick at its disposal, to promote industrial peace through collective bargaining and coordinated strategic decision making. In addition to, “…environmental pressures…”, the policy actions of the government shape the strategic choices employers and unions make.80 The Ontario government should consider exercising policy tools such as tax cut programs, upskilling and reskilling grants,81 and legislative reform. Together, these actions can serve as a carrot, incentivizing network stakeholders to contribute to behaviours that promote coordinated responses to technological change. The role of the government will be to ensure that organized private-sector workers in Ontario have access to the labour market information pertinent to withstanding digitally driven changes. For the greatest impact employers, unions, and individual employees themselves should be targeted. A triadic mapping of a policy response would require the Ontario government to align its policy efforts with negotiated, domain-specific training goals. In addition to legislative reform, the policy actions should be enforced through partial pension matching schemes, provincial government contracts, and subsidies.82 The government should use policy tools that favour the “carrot” approach to balance the tensions between the need for innovation in a changing digital market and the need for insulation from the substitution threat at work.

8.3 Bargaining Agents (Trade Unions)83

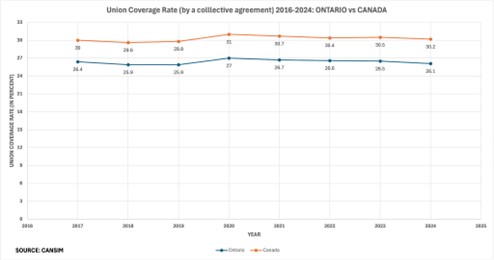

In addition to bargaining for wages and benefits, unions should pursue protections against the substitution threat for workers in collective bargaining. As a blog post from Teamsters Local 987 (2001) suggests, unions can (and should) reduce the substitution threat by, “…ensuring retraining is prioritized over replacing employees.”84 Figure 1 illustrates the continuous downward trend of union coverage rates in Ontario. With declining union coverage rates, trade unions must demonstrate their continued relevance in a dynamic labour market. Unions must (!) demonstrate relevance in Ontario by advocating for a s. 51-55 transplant,85 and collectively bargaining for terms that protect workers from substitution shocks and provide meaningful pathways for industry-specific continuous learning.86

Figure 1: Union Coverage Rates from 2016-2024, Ontario vs Canada.87

IX. Conclusion

Labour law and the industrial relations framework in Ontario are not well equipped to protect private-sector unionized workers from the intensifying substitution threats generated by automation and the digital restructuring of firms that workers face during Industry 4.0. This analysis has argued for a legislative reform and a shift towards a coordinated response grounded in Kochan et al.’s (1983) Strategic Choice Model and Hopster and Maas’ Technology Triad. While much of the labour relations in Ontario can be conceptualized through Kochan et. al’s (1983) dated model, the fourth wave of industrialization has necessitated a supplement to account for the dynamic complexities of technological disruptions. In a coordinated response, each stakeholder has a role to play. Firms must lead labour market information and efforts to close the skills gaps between machine labour and human labour. Governments should utilize a “carrot” through policy efforts to incentivize firms to prioritize industrial harmony and investing in skilling (some) workers. Lastly, it will be essential for bargaining agents to reaffirm their relevance by bargaining for worker security and continuous learning (skilling) during periods marked by technological change. In addition to strategic choices and tailored policy efforts (government, union, or management), the legislative proposal for a transplant of sections 51-55 of the Canada Labour Code,88 to the Ontario Labour Relations Act,89 creates a new floor (minimum) protection for workers in Ontario similar to the Employment Standards Act, 2000, S.O. 2000, c. 41.90 Future research should seek to study recent collective bargaining agreement provisions related to technological change in Ontario. Jim Stanford and Kathy Bennett’s (2021) study can serve as a vital starting point.91 The study might aim to understand if any of the provisions agreed to align with a strategic choice model in industrial relations, mapped onto a technology triad.